The first time visited Montalcino 17 years ago I didn’t realize where I was – in terms of the importance that this small hill town has in the Italian wine world, not to mention its importance in the entire wine world. I didn’t really have any interest in going there. It was entirely a mistake on my part that we ended up there. It was a crisp February sunny late afternoon when my friends and I went for a drive heading south from Siena. We had no plans to go anywhere in particular, but I remembered my previous trip to Tuscany when I saw an unforgettable view across a valley to the sight of the hill leading to Montepulciano. This view was from the popular inn and restaurant, La Chiusa. Not yet versed in the geography of southern Tuscany, I got confused and thought that La Chiusa was in the town of Montalcino. La Chiusa actually is in the town of Montefollonico. I told my friend that I wanted to visit Montalcino thinking we would find La Chiusa.

The first time visited Montalcino 17 years ago I didn’t realize where I was – in terms of the importance that this small hill town has in the Italian wine world, not to mention its importance in the entire wine world. I didn’t really have any interest in going there. It was entirely a mistake on my part that we ended up there. It was a crisp February sunny late afternoon when my friends and I went for a drive heading south from Siena. We had no plans to go anywhere in particular, but I remembered my previous trip to Tuscany when I saw an unforgettable view across a valley to the sight of the hill leading to Montepulciano. This view was from the popular inn and restaurant, La Chiusa. Not yet versed in the geography of southern Tuscany, I got confused and thought that La Chiusa was in the town of Montalcino. La Chiusa actually is in the town of Montefollonico. I told my friend that I wanted to visit Montalcino thinking we would find La Chiusa.

It wasn’t a total loss. It was the first time I drove along the roads of the Crete, pastureland where you can see for miles. Such scenery was quite memorable because it was one of those views that continued to the horizon. We made it to Montalcino just as the sky was getting dark. We strolled through the main street. The town had a glowing elegance as the streetlights became more dominant while the sky continued to darken. We walked through the Piazza del Popolo, the main square, with its odd but dignified town hall. As we walked towards the town hall, I noticed the Caffè Fiaschetteria to our right.

I mentioned to my friend that this appeared to be a nice little town but it was not the one I remembered from my prior trip. Sensing that I was a little disappointed, she pointed out to me that Montalcino was a notable place particularly because its wines were famous throughout the world. At the time, I knew very little about the wines of Montalcino, much less the world. But I kept this bit of information in my mind as I educated myself about the various wine regions of the world. Since that trip, I have gotten to know this area and its wines in depth.

I returned to Montalcino two years later to explore the vineyards of this wine region that held a prestigious spot in the wine world, yet carried a certain mystique about its origin. I spent a ten days of walking around the town’s medieval streets, stopping at its restaurants and shops, driving throughout the region to get a feel of the layout of the vineyards, touring a few of them and tasting their wines. As I got to know this place, I began to wonder: why did all of this happen in Montalcino? What was the reason for this town to exist in this particular spot in southern Tuscany? How did this town become such a unique and grand wine production center?

Background History of Montalcino

Although a small town, Montalcino has a long history of notable consequence. In the 20th century alone, its citizens took pride in their opposition to the fascists in the 1920s and their resistance to the Germans during World War II. During both world wars, Montalcino suffered its share of lost lives.

As you approach Montalcino from the north, you quickly notice that the town sits on a broadly sloped hill. This hill is surrounded by the Orcia and Ombrone valleys. As its history would show, geographically Montalcino was a welcoming place to settle and survive due to this hill being high enough to defend and to offer some relief from the Tuscan summer heat. The area’s first inhabitants date back to ancient times when it was only a rural settlement as testified by the discovery of Neolithic artifacts close to the Ombrone River and various locations of Etruscan and Roman tombs.

There are various theories on how the town got its name. Some believe that it was named after the goddess Lucina. Others believe it was originally called Malcenis or Malcinis because it was mentioned in a deed of a local parish church. Finally, everyone else thinks the original name was Mons Ilcinus from the Latin “Monte dei Lecci” (Mount of the Ilex) which was an holm oak tree that used to cover the hill it exists on. Ilex, the evergreen holm oak which figures in its name — from the Latin “Mons Ilcinus” decorates the town’s coat of arms.

As the Dark Ages was coming to a close, evidence of ancient settlements appeared. Foundations of some of the old churches still in existence today, such as Santa Restituta and Sesta, were around during the barbarian invasions. Later the town became part of the territories of the Abbey of Sant’Antimo, which was founded in the late 8th century, some say by Charlemagne. Montalcino was given to the Abbey of Sant’Antimo by Ludwig the Pious. These settlements developed under the feudal control of the monks. Conventional thought is that the town’s first town center developed in the early 10th century by refugees from the Maremma city of Roselle, who were chased out by the Saracen invaders.

Until expansion in 1980s, Montalcino reached its final dimensions by the 14th century. Montalcino’s grandest moments occurred between the 13th and 17th centuries during the frequent battles of the great city-states, Siena and Florence. Montalcino experienced a rapid stage of growth in the early centuries of the last millennium. The town had become considerably important, both politically and militarily, due to its strategic position on the old Francigena Way (sometimes referred as the Via Cassia running north from Rome past Monte Amiata towards Siena). This hill town was also useful to the Montalcinese as a base from which to protect themselves and harass their enemies. During this time, Montalcino, like many other small towns, was a pawn in the struggles between Siena and Florence. Although they often tried to wiggle from under the control of both city-states, for the most part the Montalcinese’s fate was tied to Siena.

After an eight-year alliance with Florence, the Sienese took control of Montalcino when it defeated the Florentines at the battle of Montaperti in 1260. Afterwards, the Montalcinese attempted several times to regain their independence, but the military strength of the Sienese usually persuaded them to back down on their claims of freedom. The people of Montalcino later were able to obtain a signed treaty of alliance with Siena which guaranteed them substantial autonomy.

Yet this did not subsequently stop the Montalcinese from starting up rebellions. All these disputes seemed to have calmed down in 1361 when Siena made the Montalcinese citizens of Siena. This was followed by a period of relative peace, during which the Montalcinese flourished in activities such as pottery, tannery, leatherworks, wool, wood and iron. In 1362, construction began on a large fortress that was designed by Ghino Foresi and Domenico di Feo for 5,086 lire and 6 soldi. This imposing fortress, designed in the shape of a pentagon, stands out above the town. Known as the Fortezza Rocca, it rises to the highest point of the city and dominates the surrounding valleys. As the 14th century came to a close, economic ties with Siena strengthened. In 1404, Siena allowed Montalcino the right to levy taxes and in the following years, Siena granted Montalcino several tax exemptions which encouraged economic development. In 1462 by papal bull, Pope Pius II, born Enea Silvio Piccolomini in Pienza, raised Montalcino to the rank of city.

The following century, however, brought war back to Montalcino. From 1526 to 1559, Montalcino became famous for standing off long sieges. In 1526, the citizens defended the city against the French under Clement VIII. In 1553 the Spanish under Charles V and the army of Cosimo di Medici of Florence, the first grand duke of Tuscany, attacked the city again. Their assault on the city failed and the citizens of Montalcino refused to surrender despite three months under siege by their attackers. Two years later, Siena fell, but subsequently, several Sienese escaped to Montalcino and proclaimed the Republic of Siena in Montalcino – the Montalcinese defiantly supported the Sienese ideals of freedom. The republic-in-exile was declared in the town hall under the guidance of Piero Strozzi and with the support of the French king, Henry II (husband of Caterina di Medici). The Sienese exiles remained in Montalcino for four years until the Treaty of Cateau Cambrésis, which marked the end of the disputes between France and Spain. The Republic of Siena at Montalcino, the last holdout from Florence, also therefore had to surrender to Florence. Soon the Medici crest was hung on the fortress wall where it remains today. After that, Montalcino did not experience much history of political or military significance. Nevertheless, Montalcino did maintain its importance as a productive commercial and agricultural center. By the second half of the 17th century, there were close to 140 shops and artisans, the city’s main activities being tannery and shoe making.

Viticultural History

Image of Brunello

The flagship wine of this town, Brunello di Montalcino, has reached an enviable level of worldwide prestige and fame. Unlike the composition of grapes in Chianti, Brunello stands on the quality of its single grape, Sangiovese. This wine has received much praised for its longevity. Because of Brunello’s quality, producers have been able to command relatively high prices for their cherished product. This reputation enjoyed by Brunello is a recent development in the last 60 years. Although Montalcino was known throughout the ages for producing quality wines, it was not until the late 1960s that key producers’ efforts that took place over the course of a century began to come together. In the 1970s and 1980s, Montalcino saw a rapid growth in the development of this wine country. Amazingly, though, this growth did not dilute the wine or upset its market value. Producers have cautiously expanded sales of Brunello gradually building stature while upholding prices.

Pre-19th Century

Montalcino has had a long wine tradition over several centuries, which is part of the great fame that it experiences today. Throughout its history, Montalcino was a farming community. Commercial and industrial development never intruded the area mainly because Montalcino remained almost cut off from the important communication routes. Over the past four centuries, the citizens of Montalcino, including several wealthy families, over time transformed the local economy into an agrarian way of life. Hence the wine tradition. The origins of winemaking culture in this area go so far back that dating them has been difficult. Some of the ancient terracing is still visible today. From ancient times, there have been writings referencing the quality of the wines from Montalcino. Their red wine during these times was called vermiglio. There is an account during the siege of 1553 when Blaisè de Montluc, a French garrison commander who was pale from hunger and stress, used this wine to rub on his cheeks to make his complexion appear healthy in order to reassure his soldiers. Montalcino was also known over the centuries for sweet wines made from the Muscadelletto grape. Even British kings Charles II and William III favored this wine referred to as “Mont Alcin.”

19th Century

While Montalcino had a tradition of wine, “Brunello” did not become the name of the red wines of Montalcino until the middle 19th century. During the 19th century, many scholars and agriculturists in Tuscany were putting a lot of research into new methods of producing a better species of vines in this region.

Just south of Montalcino, a man named Clemente Santi, a pharmacist, conducted experiments for several years on his property, Il Greppo, to see if he could produce wines that were different from the traditional ones. He eventually produced wines that were noteworthy of praise, but not yet the quality level or distinction he was reaching for. Several years later, his grandson, Ferrucio Biondi-Santi, the son of Caterina Santi and Jacopo Biondi, reached this level his grandfather was trying to achieve. Ferrucio focused on the indigenous Sangiovese grape. He believed that this grape was suitable for producing a high-class wine without mixing it with other grapes, as was the practice in the Chianti region and other regions. He used a clone of the Sangiovese Grosso that existed at Il Greppo. He abandoned the traditional Tuscan winemaking methods such as having the wine referment a second time following the introduction of lightly dried grapes. This innovation of his introduced a revolution in winemaking in Montalcino. The wine that resulted was powerful in flavor, yet delicate in texture. It was also different from Chianti.

It was around 1870 that this wine was put on the market. This new wine which was produced by using more complex and costlier procedures quickly became an élite product that was fetching higher prices than other local wines. Then came the vintages of 1888 and 1891 that Biondi-Santi produced. These two exceptional vintages became legendary which caused the prices of Biondi-Santi wines to climb even higher. The introduction of these two wines marked the coming out of Brunello as both a quality wine and an exceptional aged wine.

There were other local farmers at this time who had good results and received high praise: Giuseppe Anghirelli, Tito Costanti, Camillo Galassi, Carlo Padelletti, Rignaldo Paccagnini, the Argelini and Tamanti families. But none of them had the success as Biondi-Santi in exploiting the production of his own Brunello. There was still more development to come. Vintage Brunello was not yet a given practice year to year. From 1888 to 1945 only four vintages – 1888, 1891, 1925, and 1945 – were declared.

20th Century

Ferruccio’s son, Tancredi Biondi-Santi, carried on the family business in the first decades of the 20th century. Tancredi guided Montalcino wine producers in publicizing and marketing their wines. He also began new practices of longer fermentation and aging to establish a model of Brunello as a full, intense, and long-lasting wine. Only four vintages – 1888, 1891, 1925 and 1945 — were declared in the first 57 years of production. Biondi-Santi was the only commercial producers until after World War II. This contributed to an aura of rarity that caused high prices and an enviable prestige.

There were several episodes in the first half of the 20th century when the vineyards of Montalcino experienced several attacks of phylloxera in the 1930s. Tancredi promoted establishing a “cantina sociale” in order to meet the needs of other producers who had seen their vineyards decimated by phylloxera. Other producers, such as Ulisse Crocchi, Vieri Padelletti, Giuseppe Tamanti, Guido Angelini, and Roberto Franceschi, among others, also helped out to get new vines planted.

In addition to the phylloxera plague, World War II also left the vineyards in bad shape. Vineyards were destroyed, wine cellar equipment was out of date and the farmers were in economic dire straits. They had to start over again. Tancredi was among those who were successful in continuing the production and selling of good quality Brunello. Giovanni Colombini was another one. Colombini also contributed new and important methods in the 1950s. He knew the importance of selling Brunello in bottles instead of demijohns as was common practice. He also marketed his wines at prices that were affordable, which contributed to introducing the wine to a large number of consumers. Other estates followed. Franceschi, Lovatelli, Lisini, Camigliano, Casale del Bosco, and Castiglion del Bosco. Although production was still limited to a few thousand bottles, Brunello’s potential was recognized.

Developments in the 1960s also contributed to Brunello’s growing success. On July 12, 1963, Presidential Decree No. 930 became an Italian law. This law outlined the law on the protection of appellations of origin, known as Denominazione di Origine Controllata, or DOC. Brunello di Montalcino obtained this classification on March 28, 1966. Obtaining the prestige of this quality classification encouraged more planting of vineyards throughout the region. The number of producers was increasing so rapidly that a consortium was set up in 1967. Leopoldo Franceschi was elected the first president. The Consorzio del Vino Brunello di Montalcino has been of primary importance for the vine growing and winemaking process in Montalcino. It gives advice to the estates on the defense and protection of quality, protection of the trademark, and promotional activity in Italy and worldwide.

Then in 1969 a key event boosted Biondi-Santi and Montalcino to fame. This was a formal state dinner held for Queen Elizabeth at the Italian embassy in London. The wine selected was a Brunello from Biondi-Santi. It received raves. This acceptance put Brunello securely on the international wine map.

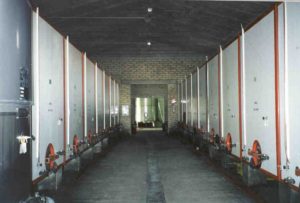

Tancredi Biondi-Santi died in 1970 and his son, Franco Biondi-Santi, continued the family business at Il Greppo. Franco made an important change to his father’s methods. Tancredi vinified the wine in small oak vats without using temperature control. Franco modernized the process by using steel tanks and temperature control. Franco was also good at public relations and marketing. Through his efforts in the 1970s and 1980s, the reputation and price of Biondi-Santi wines soared.

Other producers were also making progress in continuing the improvement of Brunello during this time. The producers of this time were upper class Montalcino residents. Most were in the same area of Biondi-Santi, just south of Montalcino. Another group of producers, only a few in number but large in their size of holdings, were located along the southern end of the region, around the town of Sant’Angelo in Colle. A third group of a few large landowners was west and northwest of Montalcino.

The 1970s also saw the arrival of a producer that has had a significant influence on the region. In 1978, the Italian-American Mariani family arrived after purchasing a large tract of land in the southwest corner of the Montalcino zone. Their company, Villa Banfi, had already made a name for themselves from importing and marketing the bulk table wine Riunite into the United States. John and Harry Mariani followed the advice of enologist Ezio Rivella to purchase this land because he believed that Montalcino was a perfect place to make a wide range of wines. Rivella was in charge of production and by 1985 they had formed an Italian wine company, Castello Banfi.

The Banfi arrival made quite an impact on the area. They brought in vast land moving equipment to level the vegetation and flatten the grade of the vineyards. Little regard was given to natural landscape that existed for centuries. A large state-of-the-art technology winery was built. The company soon acquired a nearby castle, Castello Poggio alle Mure, and changed its name to Castello Banfi. The company was criticized for not revering history the way the Tuscan did. In recent years, however, the company has become more sensitive to the historical and traditional values of the Montalcinese. Despite the initial acclamation of these foreign winemakers, Montalcino and the Banfi vintners soon became a good match. Montalcino provided Banfi with a prestigious wine appellation and product name, Brunello di Montalcino. Banfi in turn showed other Montalcino producers updated production technologies, international marketing and public relations. With its stronghold in the United States, Banfi has done much to educate Americans about the appellation of Montalcino.

On July 1, 1980, a major event took place that solidly put Montalcino and its wines at the pinnacle of world prestige. Brunello di Montalcino became the very first Italian wine to obtain the DOCG classification. Wine production growth reached stratospheric levels as the demand for these wines and the competition to produce this wine increased.

Zone Statistics

The zone of Montalcino has shown to be a region with a great vocation for viticulture. The territory, which consists of roughly 24 thousand hectares, resembles a square formed by the Ombrone, Orcia and Asso rivers. The vineyards are protected by the Ombrone valley to the west, the Orcia valley to the south and east, and the mountains of Amiata to the southern flank. These natural barriers protect the vineyards from intemperate weather, such as hail and severe storms, and help make the zone the most arid of all Tuscany’s wine regions. The zone only has about 500 millimeters (20 inches) of rainfall a year. To control the hot Mediterranean nature of the region, Montalcino experiences cool breezes off the sea, not experienced in Chianti or Montepulciano. Dangerous late-spring frosts are rare in this area. Because of this viticulturally friendly climate, it is difficult to have excessively bad vintages.

As Brunello di Montalcino slowly gained recognition for its quality, production grew along with it. Before World War II there were less than ten producers in the region. More producers came to the area and by 1968 plantings increased to a little more than 80 hectares. By 1975, there were 60 estates (only about 15 also were bottlers). In the same year, the area cultivated with vines grew to 360 hectare. Production continued to grow with a vengeance during the rest of the decade. By 1980, there were 93 estates and 650 hectares were under vines. In 1980, Brunello di Montalcino received the very first DOCG quality classification. This opened the floodgates for even more growth. According to the Consortium of Brunello di Montalcino, there are 223 producers and over 3,6000 hectares under vines.

The Process of Making Brunello

It is believed that the name “Brunello” was a local name for the Tuscan grape stemming from the fact that, in the hot, dry Montalcino summers, the grapes often acquired a brownish hue at ripening, hence Brunello, or “little brown one.” The sole grape from which Brunello is made, Sangiovese. To be more exact from a clone or several clones referred to as Sangiovese Grosso. Research conducted by the Brunello consortium with experts in nursery has identified as many as 650 different clones in use in the Montalcino region. There are many subregions within the Montalcino area, often grouped according to their soils, altitudes, and exposure to sunlight. Vineyards are typically located on steep slopes giving Brunello slow ripening conditions essential for its sturdy character. For decades the opinion of the Sangiovese varietal was that it was considered unsuitable by itself for producing high quality wines. But through their efforts to find the clones that were suitable in the Montalcino appellation, producers here were the first to show the great potential of this Tuscan grape. Their success led the way for clonal experimentation of Sangiovese in other regions such as Chianti Classico and Montepulciano. When the grapes are ready for harvest, they are entirely picked from the vine by hand.

During fermentation the grapes must remain in the vats in contact with their skins for about two weeks. Fermentation temperature is strictly controlled. The maturation process has been a distinctive factor in determining the style of wine that Brunello is known for. When Brunello became under the control of the DOC laws, a compulsory aging period of four years in barrels was inserted into the law. The period in barrel was later reduced to 3½ years. The DOC laws require that Brunello could not be sold until four years from January 1 following the harvest. If a producer sold the wine before the four years were up, he could not call it Brunello. Instead he would have to label it “Vino Rosso di Vigneti di Brunello,” which was a preview of the future Rosso di Montalcino DOC, the second label to Brunello. Riserva wines are released after five years. Traditionally, the wine was required to undergo a prolonged stay in barrels. This was considered the only way to tame the roughness of this type of grape and to give the wines their rich and sturdy character. Brunello usually has greater body, structure and color than other Tuscan wines and an ability for lasting longer.

With regard to the barrels in which the wine matures, there has been a gradual evolution over the years. The old chestnut-wood barrels have been replaced with those of Slavonian oak (of both medium and large dimensions) and, in more recent times, with French barriques (small 225 litre casks) and with tonneaux (550 litres). In recent years, the method of refinement in the bottle has prevailed.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, there has been a divided opinion on the issue of barrel aging. The traditional view held by wineries such as Biondi-Santi and other wineries closeby which believed that the classic style of Brunello based its claim to greatness on the longevity of the wine. Their wines were very tannic and full bodied that required extensive barrel aging. But other producers, such as Castiglion del Bosco, Carparzo, and Altesino and other wineries in the south and north ends of the zone, wanted to create softer, more up-front wines that did not require long cellaring. They also believed that reduced aging would help producers cope with maturing the wines of weaker vintages, which could not withstand the more aggressive oxidation rates, which are a consequence of aging in wood.

In 1998 a compromise was reached which allowed significant changes to the DOCG. That year regulations were approved that maintained the total aging of four years, but within this period the minimum time a wine must spend in wood came down to two years. This change allowed winemakers who favor the use of small to medium size new oak barrels and if all conditions are right it would also mean a very beneficial two years bottle aging before release. At the same time, it allows for more traditional wines aged for longer periods in the larger Slavonian oak casks. This 1998 amendment had retroactive effect. The 1995 vintage is the first vintage to be released with this amendment in effect.

As time passes, the color of Brunello changes: it goes from a rich ruby to garnet; then, after many years, it takes on orange-like subtleties. All during this time, however, its powerful bouquet and dry, smooth and balanced taste remain the same. There are those who believe that the highest quality level that Brunello can attain is between six to ten years after its harvest. The spectacular ones uphold this quality level even as the years pass on further.

Other DOC Wines of Montalcino

Brunello is the flagship wine of Montalcino. Yet as the boom of vineyard growth continued, producers saw it logical and necessary to diversify into producing additional wines. The three main categories are Rosso di Montalcino DOC, Moscadello DOC, and Sant’Antimo DOC.

Rosso di Montalcino DOC

Rosso di Montalcino is considered to be Brunello’s younger brother. This wine obtained the DOC classification in 1984, is the continuation of what was called Vino Rosso dai Vigneti di Brunello. It is a younger wine than Brunello using the same grape, but not submitting the wine to the long maturation period in wood barrels. This allows quicker revenues and avoids tying up capital for four years. The wine’s character is less tannic, but still full with powerful flavors. The aging requirement minimum is one year in any type of container. This wine is put on sale starting from September 1 of the year following that of the harvest. In the past fifteen years, Rosso di Montalcino has done very well. Annual production averages about 3 million bottles.

Moscadello DOC

Montalcino had a long tradition in producing dessert wines that was popular during the Renaissance. Then it was called Moscadelletto and its characteristics varied somewhat from the present day Moscadello. Over the centuries, however, it practically disappeared. A few producers, such as Clemente Santi, tried to bring it back. But it was not until the success of Brunello that producers decided to promote replantings and sales of Moscadello. Producers felt a need to produce this wine again for cultural purposes and for a continuation of the tradition. In 1984 Moscadello di Montalcino received DOC status. Production remains limited. Only eight estates currently make it. Only 50 hectares of the vine-planted area accounts for making this wine. On average, only 100,000 bottles are made each year. Moscadello is made from the white grape Moscato with the possibility of using up to 15% of other white grapes within the province of Siena. Moscadello can be either still or sparkling.

Sant’Antimo DOC

Dry table wines made from grapes other than Sangiovese had been in existence in Montalcino for several years. Sant’Antimo DOC wines were introduced with the 1996 harvest. It takes its name from the Romanesque abbey of Castelnuovo dell’Abate. Wines under this category are from non-traditional Italian grapes, such as Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir and Syrah. The DOC regulations are flexible with production technique. The wines can be either single varietal or blended. The DOC also provides for two dessert wines: Vin Santo (made from Trebbiano Toscano and Malvasia Bianca) and “Occhio di Pernice” Vin Santo (Sangiovese and Malvasia Nera). The DOC designation gave an international legitimacy to these high-quality table wines. Currently the vine-grown area is 180 hectares and production is one million bottles.