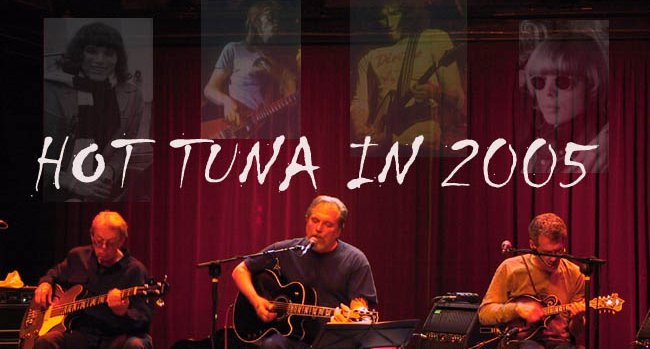

Hot Tuna in 2005: Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady’s Enduring Musical Journey

Interviews with Jorma and Jack

Hot Tuna in 2005: Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady’s Enduring Musical Journey

Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady’s enthusiasm for their music is as strong as it’s ever been in their five-decade partnership. Even with all their accomplishments and superstar fame, these two legendary virtuosi press on with the next challenge.

Earlier this year, I watched Bob Sarles’ documentary Fly Jefferson Airplane. The film reminded me of this band’s importance as well as the contribution that Jorma and Jack made with their amazing musicianship on guitar and bass guitar. Around the same time, I noticed that they had just started their Hot Tuna tour in northern France. So the idea came into my head to go to France and see how they were doing these days. They took their Hot Tuna acoustic ensemble to France and Italy for a four-week tour. Barry Mitterhoff completed the lineup with his masterful work on mandolin and tenor guitar.

I caught up with the trio in Provence to see their shows in Avignon, Arles, and Nice. Their play list included blues, country, and folk songs from Jorma’s vast repertoire of compositions as well as songs by their heroes like the Reverend Gary Davis and Jelly Roll Morton. They also played their arrangements of several traditional gospels songs. Their audiences were treated to favorites like Hesitation Blues, Good Shepherd, I Know You Rider, Keep Your Lights Trimmed and Burning, I’ll Let You Know Before I Leave, and several other classics. The energy in their performances was as forceful as it was in Hot Tuna’s early years.

As veterans of the music world, they have created a work ethic that keeps them sharp and fresh. Whether they are touring, recording, playing with other accomplished musicians, or teaching at Jorma’s guitar camp in Ohio, they have remained devoted to exploring the music styles that caught their attention when they were teenagers in Washington, DC.

Early Development

Although Hot Tuna is officially Jorma and Jack’s spin-off from Jefferson Airplane, from their point of view, Hot Tuna’s origins go back to the late 1950s when they were budding musicians in Washington, DC. They formed a group called the Triumphs with Jack on electric lead guitar and Jorma on rhythm acoustic. After Jorma graduated from high school, he attended Antioch College in Ohio where he met fellow students and guitarists, Ian Buchanan and John Hammond. Both versed in finger picking style, they urged Jorma to venture up to New York to learn from the master, the Reverend Gary Davis. Later Jorma moved to the San Francisco Bay Area and enrolled in the University of Santa Monica. He spent a lot of his time giving guitar lessons and performing in small clubs with other musicians who would make their marks on the music world.

Jack, in the meantime, stayed in DC to improve his musical skills. After he finished high school, He supported himself teaching guitar lessons. He also absorbed all he could from the blues and jazz musicians who played in the east coast clubs.

The Jefferson Airplane Years

“I thought Jefferson Airplane was the best. I thought Jefferson Airplane was better than the Byrds. Better than the Grateful Dead. Even though I was in the Byrds. I thought they were stunners.” – David Crosby quoted on VH1 Behind the Music: Jefferson Airplane.

It was as if the music gods were hard at work in bringing together the talent of Marty Balin, Paul Kantner, Jorma, Jack, Spencer Dryden, and Grace Slick. The songs they produced became anthems for a generation. Singers/songwriters/musicians Marty and Paul made plans in the 1965 San Francisco scene to form a group in which they could play an electric-style of folk music. They invited Jorma to be their lead guitarist. Reluctant at first, he soon agreed. Jorma, in fact, would be the one who came up with the group’s name. It derived from a nickname a friend gave to him, Blind Thomas Jefferson Airplane in reference to blues legend Blind Lemon Jefferson.

In September 1965, Jorma made a fateful telephone call to Jack. Jack was surprised to learn that Jorma, the blues purist, had joined a rock and roll band. Jorma was surprised to learn that Jack had recently taken up the bass guitar. The band was looking for a superior bass player. So Jack moved out to San Francisco and joined the band. He did not disappoint. Spencer on drums and Grace with her powerful singing voice (replacing Signe Anderson) completed the classic Jefferson Airplane lineup. With their songs like White Rabbit, Don’t You Want Somebody to Love, Embryonic Journey, Martha, and Volunteers, among several others, the group established their place in music history. Along the way, Jorma made a reputation for himself as one of the world’s most prolific electric and acoustic guitarists. Jack, likewise, became one of the world’s premier bass guitarists. His innovative and melodic bass playing brought the bass guitar to the forefront of rock and roll.

Hot Tuna Is Born

By 1969, Jorma and Jack wanted to return to their roots and play more of the blues songs. However, such acoustic songs did not fit in the Airplane set that had become a musical form of political expression by that point. So Jack and Jorma formed a band within the band that became known as Hot Tuna. What began as informal jam sessions while Jefferson Airplane was on tour, soon became the opening act for Airplane concerts. With the band members drifting apart, Jack and Jorma decided to leave Airplane in 1972. Hot Tuna became a their full-time endeavor while Paul and Grace formed Jefferson Starship with Marty later joining them. Spencer had gone on to the Grateful Dead’s country-rock spin-off, the New Riders of the Purple Sage.

During these years, Jorma (as he had in Airplane with songs like Embryonic Journey) continued to show his songwriting ability with songs like Genesis, Mann’s Fate, I’ll Let You Know Before I Leave, and The Water Song. The two also showcased the symmetry they created through their flawless interplaying arrangements whether they were playing one of Jorma’s compositions or their interpretation of their favor blues, country or folk songs. During the 1970s, they also added an electric element to their discography. They jokingly refer to that period as “the metal years.” In all, between Hot Tuna and their solo projects, Jorma and Jack recorded over 30 albums.

Through the 1980s and 90s, they continued performing and recording, at times briefly reuniting with Airplane members or with various well-known musicians they admired. In 1995, Jack and Jorma reunited with Marty, Paul, and Spencer when Jefferson Airplane was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. In their set, Jorma performed Embryonic Journey.

The Journey Continues

It’s apparent that Jack and Jorma are proud of and look back fondly on their association with Jefferson Airplane. For them, those phenomenal years were an important episode in their musical development. But when that band had run its creative course, they were ready to move on. By the time, they put Hot Tuna into full force, they were seasoned musicians and performers on the international stage. With their own signature, they were ready to show the world their knowledge of and ability to master the blues, country, bluegrass, gospel, and other folk music styles. They continue this journey today on stage and in the studio by examining different approaches to the music.

Another project that they have embarked on is teaching. In 1993, Jorma and his wife Vanessa began the Fur Peace Ranch Guitar Camp in southeast Ohio. They opened an facility where students musicians can receive instruction from Jorma, Jack, and several other established musicians in a four-day seminar format. They teach all levels from beginner to master classes. Their classes fill up quickly and students often return for additional instruction. Mark Robinson of Pine Bluff, Arkansas, has attended the ranch five times and said he learned something new each time. “I’ve taken classes from several of the faculty, including Jorma. The teaching level is very high. Jorma and Vanessa have created a homelike atmosphere that is very conducive for learning. You even learn just by being around so many musicians. The accommodations are comfortable and the food is excellent.” This project is nothing short of tremendous.

The ranch is only one aspect of the accessibility of these two master musicians. They both offer instructional DVDs that are available at their web sites. You can also find instructional tabs to some of their songs on the Internet. Jorma also offers detailed video guitar lessons on one of his web sites called BreakDownWay.com. For a budding musician, there’s never been a better opportunity to learn from two of music’s most important and accomplished individuals.

The careers Jorma and Jack are truly remarkable. If they had not produced anything after the breakup of Airplane, they still would have been regarded as two of the most consequential musicians of our time. But their dedication to the music that gave them great joy inspired them go forward and investigate where they could go with an art they thoroughly understood. This attitude is apparent today even after a few dozen albums. On top of that, they are sharing their knowledge and appreciation to present and future generations of musicians. Jorma is the only guitarist on the Rolling Stone top 100 guitarists list who has a music camp where students can learn from people of Jorma and Jack’s stature. This is unprecedented. Jorma and Jack represent a genuine spirit of the blues: learning from the experts who came before them, perfecting what they learned, and then passing it on to those who are ready and willing to continue this rich tradition.

########

Interviews with Jack Casady and Jorma Kaukonen – Grand Hotel Nord-Pinus – Arles, France – March 18, 2005

Interview with Jack Casady

Joe Pascale: I won’t be in Italy when you guys perform there in a few weeks so I had a few days free to come and see you play here in France. I caught up with you yesterday in Avignon.

Jack Casady: You saw us last night in Avignon?

JP: Yes.

JC: That was a fine place to play. A wonderful place to play and the people were just terrific. And the sound system was terrific. We’ve had really nice conditions so far. We’ve done seven or so shows so far.

JP: You still have about seven more here in France, right?

JC: It’s about a 28-day tour with three weeks in France and one week in Italy. So we’re really enjoying ourselves. Jorma and I were just talking the other day about how interesting and open the people are, but also how knowledgeable the French people are about the music. They’re used to listening. They like jazz. They like blues. And they’re used to coming to a club apparently, listening to the musicians play, and the interaction of it. And they appreciate it. We’re very grateful to play and have that situation. It’s very gratifying. Jorma and I have been working on this style that we’ve created for many, many years. Of course, he and I have known each other a long time and actually played in a band together in 1958 —

JP: — The Triumphs —

JC: — Yes, we’ve known each other a long time. But, the upshot of that is – we were commenting – it’s better then ever to play now. I wouldn’t go back in time, if I could. I’m a much more complete musician now. So is Jorma. We really enjoy the music we are making and the way we are doing it today. And, of course, we have great support. Barry Mitterhoff is with us on mandolin and tenor guitar for this acoustic series.

JP: How often are you guys getting over to Europe?

JC: Jorma and I have not done it together for quite a while. We started up again about three years ago. Jorma had been coming over a number of years ago, a number of times. He and I hadn’t really played regularly over here for a long time. Actually, these last couple of years we’ve played more in Europe than we had and we’re going to continue doing it.

JP: Once a year?

JC: Well, it seems to be working out that way. Last year was primarily Italy, the year before that was mostly Italy with a show in France. We played the New Morning jazz club in Paris last year. This time we did a full tour in France and it has opened up a whole new world for us and we’re really surprised and happy that so many people have been coming to all the shows. Next time, we’ll mix up our venues.

JP: Teaching appears to be important to you.

JC: In the last eight years, the format of the Fur Peace Ranch that Jorma and his wife, Vanessa, who is also our manager, set up on his property in southeast Ohio is a wonderful facility for teaching. It has a concert hall plus a fantastic music library and teaching facilities. Usually, we’re there for a long weekend. We do Friday, Saturday, Sunday with a wrap up on Monday. A student can be anywhere from 18 to 88 years old.

JP: At all levels of skill?

JC: All levels. We give them an opportunity to immerse themselves in the music, where in the real world, life will interfere with your ability to do that. So just that chance to have four days of concentration on some concepts that we’re teaching allows that student to walk away with something he can hang onto and put to use in his own format. And it’s really helped our playing. It’s helped my playing immensely to have to break down all that I’m playing and why I’m doing it and reconstruct it in order to explain it to people. Of course, it makes me practice much more than I normally do and I put in eight hours of teaching and I really know my instrument pretty well myself. I started out teaching when I was about eighteen in Washington, DC. It was in a guitar store and it was mostly a means by which to get out on my own to get my own apartment. I enjoyed it, but I never really got back to it until Jorma invited me to teach at the Fur Peace Ranch when it opened up eight years ago.

JP: You grew up in DC.

JC: Reno Road and Davenport. My house was right next to Murch elementary school and then there’s Alice Deal junior high school up the corner and then there’s Woodrow Wilson high school. Jorma and I went to Woodrow Wilson together, of course. And I went to all three so I never took a bus ride.

JP: Do you find that young musicians today are interested in playing the blues and rock and roll the way you guys played it?

JC: Some of my earliest influences when I started playing the guitar around the age of twelve were Bix Beiderbecke, Jelly Roll Morton, jazz players that played in the 20s and 30s in small combos I really enjoyed. Later on, people like Ray Charles and rhythm and blues players, Amos Milburn, people like that and then, of course, the early rock and roll. You know, you can always can count on youth to explore and I think that more than ever there’s more preserved in the music catalogs today. There’s quite a variety of young musicians who aren’t into the rock and roll world – the mainstream music world. But they’re interested in the history of music and search out the various players and the original versions of those songs. So if they’re interested in the blues, it’s up to the inquisitive young player to explore back in time in recorded history to hear the earlier influences of the later musicians that they may have encountered. The young ones are never going to see most of these musicians play live again and they’re going to hear other musicians with those influences, but they have the opportunity to search it out and to hear the earlier influences and then to absorb that, hopefully, so that they develop and create their own style and approach to music.

JP: What are the main projects that you’re doing now?

JC: I was away from home on the road 230 days last year. That’s a lot. I live in Los Angeles. That includes going out to Fur Peace Ranch five times a year, sometimes six times, for a week at a time. And then Jorma and I tour a number of times each year. Then I have other projects. I did my first solo album, Dream Factor, two years ago and I’m working on material for the next one. I have my own recording studio at home like so many musicians do today because you can and I enjoy that. So between that, teaching, and working on the road, my time is filled up and it’s better than ever. I enjoy it more than ever.

JP: How have you and Jorma kept playing together fresh after all these years?

JC: I think it’s the communication between the musicians. It’s always about that. It’s always about listening to the fellow next to you playing. That is what is important to keep it fresh. Get a little influences here and there. Listen to yourself and don’t allow yourself to get in a rut and play the same thing night after night. You can do little things. You can change the tempo a little bit from night to night which will put you in a different frame. You can mix your songs up and we have quite a vast library of songs. Like in a tour like this, we don’t repeat those songs a lot as a regular set. We don’t do the same thirteen-song set every night here in this format. That’s important. A lot of what’s made it fresh for us is teaching these last number of years.

JP: How has the teaching kept your playing fresh?

JC: Well, it requires that you investigate your own technique and the way you go about playing and the way you think of how you construct the music and put it together. So as you shore up the weaknesses in your playing, you also find yourself playing – at least for me – new approaches and coming into the music from a little different direction. I’m much more thrilled about just placing the notes in a more simple way to make the song hold up than I am about, perhaps, a fast solo. Although, I do what I call melodic solos. The soloing aspect to me – it’s very hard to explain how I do it – I try to actually listen where my music is going as it’s going that way while I’m constructing the solos and to see where it takes me. Again, it’s listening to what you do and imagining the melodies and creating them on the spot.

JP: Is that what’s referred to as the music is playing the musician?

JC: Well, to a certain extent. You have to have all your senses sharp and aware. It’s not just a matter of just dulling your senses to go on to endless playing. I enjoy being clear today, if you know what I mean, and playing and being comfortable with myself. So it’s really a great time to play music for me. I feel like I’ve never had my application to the music as fine tuned as it is now. So I hope to keep raising the bar myself and keep going up with that.

JP: You’re well known for your melodic style.

JC: I don’t like to think of it as solos. Like everybody leaves and then I’m hung up to dry out. To me it’s just like an orchestral part where a different part of the orchestra will play. A cello portion comes in with the bass, then the melody shifts over into that area of the music and then it will all go back into a support area. Now I’m able to do that in this style in this format because the finger picking style of Jorma Kaukonen keeps not only the pulse or the rhythm together while I’m doing that, but also – it’s like having two hands on the piano. He’s able to make a lot of music that way and the music still holds it’s integrity when I move from the low end up into a mid-range or up into a cello range in order to play some of the melodies that come within the song. When that happens, then he will shift down to support at the same time – the structure of the song holds up. It’s a lot different if I were playing only with a linear guitar player that either played linear lines or rhythm back and forward like the standard most guitarist play with a pick, then you need the rhythm section behind you to hold those licks and forms together and it’s a different style of playing. I’ve played that style before.

JP: You don’t care for the standard style anymore.

JC: Yes, I enjoy doing it, but I enjoy this much more. This is much more challenging and much more open and I’m able to use a lot more of my faculties for it. Not to take anything away from anybody else that does that approach, but not many can do this approach that we do as a duo or as a trio in this case with Barry.

JP: What influenced your melodic style?

JC: Well, I call it the bass guitar. It’s not a standup bass. When I first encountered the bass guitar around 1959, I was playing guitar as well and I had to fill in for somebody and played with a friend of mine, Danny Gatton, who has passed on now, and I filled in with his band in Washington for a couple of weeks playing bass guitar and I really fell in love with the instrument. I really liked the tone. I bought myself a concentric pot pickup 1960 jazz bass. I also did a lot of listening to players like Eric Dolphy and Roland Kirk who brought a new tone to their instruments. They were always challenging the instrument and themselves. To listen to Eric Dolphy on bass clarinet was just wonderful.

JP: Mingus was a favorite of yours.

JC: Charles Mingus was a favorite of mine as well. Now I didn’t really try to emulate too many bass players, but I did like a musician who came up with his own tone – whatever instrument he played. So I think that was a big influence to me to just play what I started to hear in my head. And I’d transfer some of these things I’d hear that normally would be done on a higher range instrument onto the electric bass. Because first of all you can play up in the electric bass and be very articulate as well as trying to balance that kind of melodic playing and at the same time support the song. So as I go through my career, it’s very important to always work that balance like a seesaw of pulling a melody up just enough to suspend the structure and then come back in on the down part of the song and keep the groove going no matter what. No matter what I try, you always have to keep the groove going. So if you break the groove by going off into a melodic fit of some kind, then you’re doing too much.

OOOOOOO

Interview with Jorma Kaukonen

JP: How are you enjoying the tour so far?

Jorma Kaukonen: I think it’s really been going great. It’s interesting to me because this is the most extensive tour that I’ve ever done in France. We had only been to France once in the last ten years. But in any case, the French audiences, they’re really into it. They really listen to the stuff. It’s not that they’re reserved like the Japanese are. They just really listen and it’s really cool because you play in the States and in a lot of places where we love to play, but they take you for granted and they’re just happy you’re there. It’s a different thing altogether. And of course, the food is superb.

JP: Yes, I agree. Coming here means a change in cuisine from Italian food.

JK: Yeah, right. You know, Jack and I have been touring together in Italy for the last couple of years, but I’ve been going there for almost a quarter of a century and I just really love it. It’s a different trip entirely, but I really like it a lot too.

JP: Have you played in Florence?

JK: I haven’t played in Florence the last couple of times we’ve been there, but I have played there before.

JP: Do you think the next European tour you’ll have more dates in Italy than you did this time?

JK: Usually, like last year, we have a huge tour in Italy. We had the same kind of tour in Italy that we have in France right now. I think what happen this time a friend of ours heard that we were coming to France so he put together a tour.

JP: It was good to see Bob Sarles’ Fly Jefferson Airplane DVD came out last year before Spencer Dryden passed away early this year.

JK: It’s easy to say this when somebody passes away, but Spencer really was sick and if there’s a better place, he’s there. He was really miserable. The good news is that in the last couple of years, Spencer and I reconnected. It was funny because one of my students at Fur Peace Ranch was one of his nurses at the hospital so I was able to talk to him. He sort of maintained his ascorbic wit to the bitter end. Regarding the Fly DVD, Bob’s great guy. He’s a professional filmmaker and I thought he did a great job with the Fly DVD. There’s a lot of great footage in it and it’s really pretty much about the music, which to me is what it’s all about. Everybody’s got war stories. Who cares? Let’s talk about the music.

JP: With your background in blues, have you ever been down to some of the landmarks on the backroads of the Delta?

JK: I have never really done it. Some of my friends went down there. A friend of mine named Steve James, who lives in Austin. When some of the guys were still alive, he went down there many, many years ago and he’s actually written books about it. I’ve never done it and one of the things that was funny to me – because it’s something I’d like to do and I don’t live that far away so it’s something I should do. It would be a great motorcycle trip. Anyway, we were driving to up to Nashville and I pulled off in Meridian, Mississippi, and I thought, “Wow, this is Jimmie Rogers’ hometown.” So I went and found his museum and all that stuff. From a musical point of view, it’s really profound stuff. For our opening week at the ranch, we had Mose Allison. I’ve been a huge fan of his for years. I’d never met Mose before, but his son John is a friend of mine and he talks about when he goes to visit his dad’s place in Mississippi – it’s a plantation for real. Do you know John Cephus? He’s one of the Piedmont style players. He’s probably a little older than me, but in terms of his music – you know he’s one of the last remaining guys alive – but the thing that’s really interesting is that his style is very distinctly Piedmont, but he’s continued to grow. He’s a cat that’s learning all the time. When he came to the ranch, he had a GPS in his car, he’s into his computer and email. He’s so cool. But when he plays music, it’s the real deal.

JP: Do you find that many young musicians today are interested in learning old school rock and roll and blues?

JK: It’s interesting because I’m sure there are young blues cats coming up and doing a lot of this stuff. But in my experience, I find that a lot of the tradition is really being carried on by guys whose main art form is like bluegrass and stuff like that. There are a lot of guys from the South that really know a lot about the blues and can play, but it’s just not their thing. There’s a mandolin player who Barry knows named Mike Compton from Mississippi who plays with a lot of guys. Great, great player. But when he plays stand up guitar, it’s like Mance Lipscomb was alive again. It’s unbelievable. But that’s not his thing, he does it occasionally if the gig allows it. But mainly he plays mandolin. So there are a lot of these string players, especially from down South who are just steeped in that kind of music. So it’s alive and well. Here’s another guy – Alvin Youngblood Hart – just a young guy that in my opinion is just as real as they come. He plays great rock and roll and all kinds of stuff, but when acoustic blues, it’s like being there in the Delta.

JP: Are there young students coming to your ranch?

JK: There have been a couple of kids, I’m mean young teenagers, that really understand the music. I’m not sure where they’re going with it, though, because one of them is in the Berklee College of Music now, which means he’s probably studying jazz or something like that and the other one ended up in Loyola University in the classical music program in L.A. But still, it’s there. It may pop up again.

JP: It appears that touring and teaching are taking up most of your time these days.

JK: That’s pretty much it.

JP: You’ve said in other interviews that you were seduced by the electric guitar sound.

JK: Jack and I talk about this too. The rock and roll thing – to me – volume is part of the music. It’s part of what makes it work. And it’s very, very physical. It’s one of the things that at this point in my life, even though we’ve been doing some electric gigs, that, as a full-time thing, I don’t find so attractive. It just physically hammers you, which is, in some respects, why it’s a young man’s game. But it’s really important that you be slammed around by the music. But with the acoustic, it’s not quite as visceral a thing. But certainly, like I’ve said, there is something seductive about being totally physically involved in a music form.

JP: How do you keep performing fresh?

JK: Certainly we all get into ruts sometimes. But the good news is that music is an endless learning process and I get to play with a lot of different guys so I learn lots of stuff. It gives me different insights into some of these same old songs so they never really stay the same. I mean, we joke about the things like I almost don’t even like music that’s newer than 1930. But there’s lots of ways to approach these songs and there’s always new levels like, “Wow! I never heard that before. Check this out.”