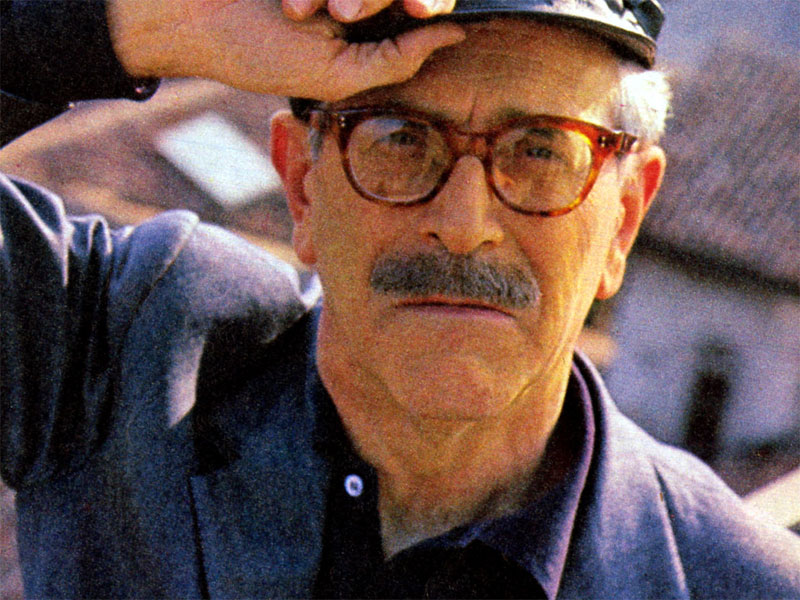

Burton Anderson has been called by many, including other world renowned wine experts and journalists, the leading authority on Italian wines. As an established journalist and editor from the Midwest living in Italy for more than four decades, he wrote many important articles and groundbreaking in-depth books on Italian wine. When the Italian wine industry was experiencing a renaissance which was revving up in the 1970s, Burton was right there to write about it and provide a road map for his readers in understanding the vast and confusing subject of Italian wine. No one had achieved this before him. He received critical acclaim for his work and quickly established himself as the most informed writer on Italian wine. The New York Times called his first book, Vino: The Wines & Winemakers of Italy (1980), “the standard reference, in Italian as well as English.” In 1990, his masterpiece, The Wine Atlas of Italy and Traveller’s Guide to the Vineyards, was published. Among other prestigious awards, he received the James Beard Award for Writing on Wine in 1990. In 1994, he completed and published Treasures of the Italian Table. The following year, this book earned him another James Beard Award this time for Writing on Food.

I don’t remember when I first heard about Burton Anderson. But, I do recall that I was still living in Washington, D.C., when I bought a copy of The Wine Atlas of Italy. It was a helpful guide to have with me when I visited the wine regions of Italy while I lived there for seven years. Just a few months after I earned my WSET Diploma in London and a few weeks before I moved back to the United States, I visited him where he lived at the time in Tuscany. I never published this interview because I moved to New York at the end of 2007 to work in the wine industry. So I put my website aside. But I’ve held onto the tapes of this interview. Now, twelve years later, I am publishing my two-hour interview with him in three parts for the first time. In Part One, we discussed his background, career, and writings. In Part Two, we discussed in-depth his thoughts on Italian wine. In this last installment, we finish up talking about Italian wine history and Italian cuisine. Here is Part Three:

* * * * * *

October 18, 2007 – Loro Ciuffenna, Italy

JP: What are your thoughts on certain key events in Italian wine history over the last forty years? For example, the serving of Biondi-Santi Brunello at the 1969 diplomatic dinner at the Italian Embassy in London with Queen Elizabeth in attendance.

BA: Certainly there was the rise of Brunello following that. When I first lived in Italy, nobody knew Brunello including many Tuscans who didn’t know what Brunello was. Didn’t even know where Montalcino was. Montalcino was the poorest town in the province of Siena per capita. I remember that dinner. Giuseppe Saragat, the President of Italy, was at that dinner. Queen Elizabeth tasted the wine and liked it. The fact that this happened kind of turned on some of the British writers that they made notice of it. Veronelli had started writing about it here. Previously there hadn’t been hardly anything written about Brunello at all.

The first time I read about Brunello was in Mario Soldati’s book, Vino al Vino, which came out in the 1960s. He visited those wineries and talked about them and the fact that they had these wines dating back to 1888 and 1891. That became a legend that boomed into this current Montalcino thing, which to me has its good and bad points. The good is that they are exploiting an area that to me has extraordinary potential for Sangiovese. But because they are doing it in a way that has been exaggerated, in many cases the wines aren’t up to its reputation. I’m not saying that Biondi-Santi necessarily makes the best Brunello. He makes what I would consider the most traditional distinctive Brunello. I would say that most consumers would probably would prefer a different type of Brunello – let’s say the more modern style of Brunello.

JP: But the criticism of many of the modern styles of Brunello is that they do not have the longevity that Brunello is traditionally known for.

BA: Right. But they don’t know that yet. Time will tell. I think you’re right though. I don’t think a lot of these Brunellos that are being made today will last more than twenty years, if that.

JP: Do you recall the period in the 1970s when Sassicaia and Tignanello first hit the market? I’ve heard stories that a bottle of Tignanello back then only cost five dollars.

BA: Very, very important. I think I bought my first bottle of the 1964 Biondi-Santi Brunello for something like three dollars, which was considered astronomical at that time. Sassicaia when it came out didn’t really make a big impact outside of Italy until a Decanter tasting event in London where everybody including Michael Broadbent rated it the best wine of the tasting. They took it for a great Bordeaux and that baffled everyone.

JP: Who coined the term Super Tuscan?

BA: It wasn’t me as far as I know. Although my former publisher at Mitchell Beazley said it was. But I think somebody else used it before me. I started using it in the late 1980s. It might have been David Gleave who is Canadian who used it first. He wrote actually a very good book on Italian wine in the 1980s. He’s a Master of Wine.

JP: Do you recall when the Americans, the Mariani family, got involved with Riunite to sell Lambrusco as a high-volume wine? Many smaller-volume Lambrusco producers believe that this hurt the quality and reputation of Lambrusco.

BA: That’s one of my favorite wines to sit down and drink. I adore all those wines. I have no qualms about it. In the United States, I think they are just starting to sell a few serious Lambruscos. I don’t think the Marianis could believe it themselves. It just took off. They had television adds: Riunite – it’s nice on ice. They didn’t even associate it with being wine. At that time they had wine coolers, it was sort of like the most popular wine cooler at one point.

JP: When Angelo Gaia started to use international grapes, his competitors considered it blasphemy. What you do recall about that?

BA: Yes, he planted Cabernet and that was in 1978 or so. He didn’t tell his father, who was mayor of Barbaresco, that he was doing this. He planted the hillside actually below the family villa in Barbaresco with Cabernet. Every time his father walked by it, he’d exclaim, what a shame! But this was typical of Angelo. He had this spirit. He had to be doing something all the time. He was so dynamic. I’ve never met a more dynamic person anywhere. He just wasn’t content. The reason he gave me why he did it was – he said, look I know Barbaresco. It’s a great wine and it will someday stand with Burgundy and Bordeaux. But nobody else believes it. So how am I going to prove it? First, I’m going to make a Cabernet that’s as good as Bordeaux.

JP: What was Gaja’s reputation before he started producing Cabernet? Was he already known as an innovator? Or was he just another Barbaresco producer?

BA: When he took over which was in the early 1970s, his father had run it in the traditional way and they were very respected. Considered among the best. He also made Barolo. Angelo said, no, we’re not going to make Barolo anymore because we don’t own any Barolo vineyards. We’re only going to make wine from our own vineyards. That was the big change that started it all. He learned English in about three months or so and started going around the United States and everybody was so amazed by this guy that his wines were taken seriously. They were a new style with barrique. They made a huge impact. He was certainly in the early 1980s the most important Italian wine figure in the United States. Antinori always had a noble reputation and very much respected, but Angelo had that dynamism that people just loved to interview him and write about him.

JP: When the introduction of the DOCG law came into play, do you think it succeeded in correcting the problems of the DOC?

BA: Not really. I think it did a lot of good in a certain few cases. I think it did a lot of good for Vino Nobile di Montepulciano. Vino Nobile by the end of the 1970s was a disaster. The only good one was Boscarelli.

JP: Did the Gorizia Law in 1994, which introduced the IGT classification, have a meaningful effect on classifying wines?

BA: It did put a bit of sense into the classification system. It had a certain positive effect in the sense that up until then wines were just simply vino da tavola meant absolutely nothing being the lowest category of Italian wine. It was kind of silly to have Sassicaia designated as a vino da tavola. The thing is that the whole classification system in Italy is kind of a farce. When you get down to it, the only real mark of quality and integrity in wine is the individual producer’s reputation. I’ve always held that. The fact that you are making wine that is DOCG doesn’t really tell you anything.

JP: Some quick questions about Italian cuisine. When you first moved to Italy, American’s knowledge about Italian food was limited. But Americans’ understanding has come a long way since then. Was that a surprise? Or did you see it similar to Italian wine: something that you could see then that was eventually going to happen?

BA: That was another thing that living in France convinced me of. Pretty much the same story. I adore French food. Haut cuisine was the maximum. But you travel around and ate around the country in France and you didn’t eat as well as you did all around generally in Italy. You certainly didn’t get the variety. I can’t say that I saw it coming or predicted it. But I guess I did see it coming because I always preferred it and I’ve always thought that Italian cooking should not be promoted on a national basis, but on a regional basis.

JP: Are there particular Italian dishes that are your favorites?

BA: I get more and more into fish. I adore fresh fish, but I’m very picky about it. I’ll only eat fish that was fresh caught that day. I mainly go down to the coast. The place I eat most often is called Ristorante da Anna in Castiglione della Pescaia. Fairly unknown, but everybody in Castiglione knows about it and they all know that everything there is caught that day. All the difference in the world. Other places, I adore the cooking in Piedmonte especially this time of year when you get the white truffles. Places like Puglia, Liguria, and Tuscany are fantastic. However, Tuscany however can be a pit too uniform at times, starting out with the salami and tagliatelli and beefsteak. But the product here is great if it is done right.

JP: Your views on Italian cuisine seems to be similar to your views on Italian wine in the sense that you appreciate the history and traditions yet at the same time you admire chefs who try something innovative without losing its traditional identity. An example of that is Fabio Picchi in Florence, who cooks traditional Tuscan food but adds his personal touch to the dish. Are you seeing other examples of cooks who are also doing that?

BA: No. Unfortunately, when eating out I’m finding more who miss the mark than those who are getting it right. If somebody is a creative genius and can take a good basic product and can turn it into something sublime, I like that. But I don’t see many people doing that. I’ve eaten at too many places where people say it’s really great – chef’s a young guy coming up. Then I go there and my reaction is disappointment. It’s imitation Enoteca Pinchiorri or an imitation of another top restaurant here in Italy and they’re not doing it right.

I think what they are missing is just taking the basic product and leaving it the way it is, but enhancing it a little bit with just a touch without changing its basic character. I just ate two nights ago at a restaurant which is the Alain Ducasse restaurant in the L’Andana, Hotel Castiglione della Pescaia. I went with the owner of da Anna and a wine guy who I know. I mean here’s a Frenchman, maybe the most famous French chef right now, coming into Tuscany and calling it Trattoria Toscana. It’s high end. Mainly Americans. It’s serving these dishes which miss the mark. It has a French chef. Young guy. Nice guy. Good chef. But they are missing the mark. If they are going to call it Trattoria Toscana, they should really do Tuscan food. He’s doing a French interpretation of traditional Tuscan. It’s heavy. It just doesn’t work.

JP: Last three items: first, olive oil. Do you think the varieties of olives will ever be understood to the level that wine is? Several people in Tuscany tell me that they would like to see that happen.

BA: No. I think the main thing about olive oil first is that you have to realize that it’s a product that doesn’t age well unless it’s made in a certain way. The best way to make it – I’ve changed my views completely on this – is not the traditional way, but in a modern way. Pressing the olives within hours after it’s picked in an oxygen-free environment and then bottle it. That way you can make olive oil with all its basic character intact, lowest possible acidity. It will have flavors and quality that will last for years. And it doesn’t cost any more to do it that way. In fact, they have new equipment that is affordable and can be put in your basement.

That’s where the future should be. But the problem is that even here you go to a supermarket and you can’t spend more than €8 for a liter of all the stuff they offer that’s indistinguishable. Luckily, now they have to say on the bottle that it comes from Italian olives and if it’s from a DOP area it has to come from olives there. But 90 percent of the ones sold here is just crap. Even Tuscans themselves when they run out of olive oil, they go and buy this cheap stuff.

JP: Are we going to lose these varieties of olive oil?

BA: I don’t think the varietal factor is as important in this case as the processing. It’s interesting what some estates are making olive oil according to varietal and it’s very interesting in terms of their quality and something that ought to be followed up on but only if you are using the modern method because then the quality remains intact. But you are not going to see a lot of this because they don’t make enough money out of it except for large volume producers.

JP: Traditional balsamic vinegar. Everyone is aware of balsamic vinegar, but not so much about traditional balsamic vinegar. Do you think it will become better understood?

BA: I think because it’s such an elite item, worldwide understanding of will be limited. It’s only small production and you are only going to find it at top shops and top restaurants and it’s expensive. But you can’t expect to promote it. It’s been overwhelmed by what was the biggest mistake probably they ever made in food regulations in this country which was allowing all the other stuff to be called Aceto Balsamico di Modena. Because the only other thing distinguishing the good stuff and everything else is the word traditionale. Otherwise, it’s the same. And everybody thinks, oh! that’s the brown stuff that’s sweet. When the regular stuff has nothing to do with the great balsamic traditionale. They really ought to call the regular stuff something else. That is one of the chapters that I have in my book, Treasures of the Italian Table.

JP: Last question about Italian rice. Do you think Carnaroli, Vialoni Nano, or other Italian varieties will eventually become widely available in the U.S.? Because now they are difficult to find.

BA: Rice is another thing I wrote about in 1994. I don’t know how that market is developing. I know that good risotto even in Italy isn’t widely made. The best is supposedly Carnaroli and a few others. There’s a chapter in that book about the situation thirteen years ago and I don’t think it’s changed very much since. I don’t think there’s much awareness about it. I think people think they can take Uncle Ben’s and make risotto with it.

JP: Hopefully people coming to the risotto regions on vacation will help spread the knowledge about how good risotto should be made.

BA: When they go places that make really good risotto, but there aren’t all that many places that make really good risotto. I mean you’re not going to see many chefs standing over a pan and stirring risotto for the amount of time it takes.

*********