It is helpful to spend some time learning about wines that are benchmarks – those wines of the world that are regarded as the most prestigious. I may never have the privilege to taste some of them, but I find that knowing about the wines regarded to be in the top stratosphere gives me a context in which to understand what all is out there in the world wine market – what standards have been set. Also to learn what history and the market have chosen as the wines of the highest distinction. Last spring while I was in France, I went to visit the sacred ground from which one of those celebrated wines is born: Romanée-Conti.

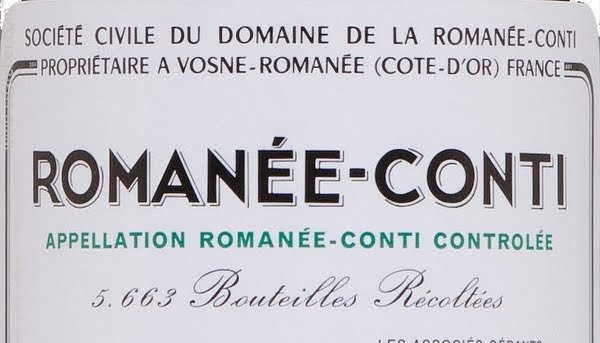

Romanée-Conti is the most prestigious wine of Burgundy located in Côte de Nuits. It is a grand cru, the highest appellation of the Burgundy Appellation Contrôlée system. It commands an astronomical price. A young bottle of Romanée-Conti can easily set the purchaser back $3,000 for a bottle, and that’s on the low end. Oh, yes. That is what you would have to spend – if you can find it (not impossible, though: Internet). This 4.5 acre plot of land produces on average 5,940 bottles each year.

The vineyard is one of the seven grand cru wine properties owned by the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti (DRC) estate based in the little town of Vosne-Romanée. DRC, or “The Domaine”, is co-owned by the de Villaine and Leroy families. They have had joint ownership of La Romanée-Conti since 1942. Although the estate prospered, this joint ownership was a source of conflict for several decades. For one, Henri Leroy’s négociant business was granted the exclusive distribution rights to DRC wines in all markets except the USA and UK. However, the de Villaine family at times resented this arrangement. It was the co-directorship, beginning in 1975, of Lalou Bize-Leroy and Aubert de Villaine that brought this conflict to a head.

Lalou is a passionate and highly-skilled winemaker. She has been referred to as the “Queen of Burgundy”. She worked closely with DRC’s cellar masters, first André Noblet and then his son Bernard. She worked hard to maximize the quality of DRC’s wines which were released at astonishing prices. For example, in 1990 Romanée-Conti was released at a record $900. Her family’s distribution power gave her control over both production and sales. This power, ironically, resulted in her dismissal as co-director of DRC in 1993. She was dismissed when Aubert de Villaine and her only sister Pauline Roch-Leroy decided to replace her with Pauline’s son, Charles Roch. Charles was soon succeeded by his brother Henri Roch when he, unfortunately, was killed in an auto accident.

The reason for Lalou’s dismissal had to do with the way DRC wines were sold by the Leroy distribution business. DRC wines were only sold in lots of one bottle of the sought-after Romanée-Conti packaged with 11 slightly less glamorous DRC bottles. This pricing structure resulted in serious marketing problems in the early 1990s. In the late 1980s, the Japanese took a grand interest in wine and began buying up all the top wines they could find. When it came to DRC wines, they were only interested in Romanée-Conti and they didn’t care what they had to pay for it. The Romanée-Conti was sold at an exasperating price. This left the DRC wine distributor with a huge profit and a glut of non-Romanée-Conti DRC wines. The distributors then sold these wines at very cheap prices – prices that were much cheaper than what American consumers had to pay for it. The consumers were mad at the American distributors and the distributors were mad at DRC. They even threatened to sue. Lalou was blamed for this fiasco. She retained her 25% ownership interest in DRC; she’s just wasn’t running the show anymore.

Despite public embarrassment, Lalou soon landed back on her feet no further than the other end of town. She now owns Domaine Leroy. She wasted no time in bringing her wines to stand toe to toe with the wines of Romanée-Conti both in terms of quality and price. At Domaine Leroy, Lalou incorporated a controversial form of viticultural practice, biodynamism. The controversial aspect about this method is its belief in the influence of the cosmos and constellations on different aspects of the plant’s growth. The winemaker then plans his treatment of the vines according to the positions of the moon and stars, the time of year, and even the time of day. These winemakers like this claim that by obeying these rhythms of nature, healthier vines are produced and hence better wines will result. Lalou received a lot of criticism for this approach, but her resulting successful wines silenced her critics. Now, some other estates in Burgundy are using this method.

For all practical purposes, the red wines of Côte de Nuits are made solely from the Pinot Noir grape. It is one of the most difficult grapes to work with when attempting to produce high-quality wine. Unlike Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, or Syrah, Pinot Noir has not been as easily transportable to other parts of the world from its original territory. It generally produces the best quality wine on limestone soils and in relatively cool climates where this early ripening vine will not rush towards maturity, thereby preserving aroma and acidity. Often, producers willing to take on the challenge of producing Pinot Noir, often fall short of the mark. Jancis Robinson, one of the leading wine authorities, has said that four out of every five Pinot Noirs she’s tasted have turned out to be a disappointment. However, when it is done well, the experience is sublime. These wines include the richest and most elegant red wines of Burgundy. They tend to be perfumed and velvety when young, deep and more vegetal if mature. At its most complex, the flavor will have nothing short of an ensemble of raspberry, red currant, cherries, strawberries, prunes, roses, violets, truffles, liquorice, vanilla, cinnamon, and musk.

Having learned the history of this notable field of vines, it was one of my first stops while I spent a few days driving up and down the Côte d’Or. Luckily, it was a clear, sunny day in the comfortable temperatures of April. When I walked around to take these photos, there were a few tourists who were making the same stop. It is possible to drive right up to the vineyard, and if it’s not busy with either workers or tourists, you can park your car along the road so you can take the time to absorb the place.

Approaching from the town of Beaune, the commercial capital of wine from the Côte d’Or, it is no more than a half-hour drive to reach the vineyard. Driving north on R.N. 74, you can turn off to the left when you reach Vosne-Romanée. It doesn’t take long to cross over to the western edge of the village. Once on the western edge, if you drive about another 150 yards, you will find yourself at the southeast corner of La Romanée-Conti.

That evening, I was back in Beaune for dinner. As I was eating my foie gras, I thought about the frustration I felt, like many other wine lovers, about the fact that I may never have that moment of enjoying a vintage of Romanée-Conti. Sure, there are several other more affordable red burgundies to enjoy, but after just having seen “The Vineyard”, I had Romanée-Conti on the brain. I wondered what I could do without getting into trouble in order to take away with me something to remember about the vineyard since I couldn’t take home a bottle of the wine. I couldn’t think of anything.

I decided after dinner to drive back up to the vineyard. Maybe along the way or when I got there I would think of something. In a few minutes I reached Vosne-Romanée. There wasn’t a villager in sight. Soon I was exiting the west side of town and approaching the vineyard. It was very dark. The only light nearby was from a crescent moon from the eastern sky, a few street lights from the village 150 yards away, and my headlights.

I drove up to the southeast corner, turned off the ignition and got out. It was noticeably chillier now. There was no sign of anyone out that night. I sat down on the wall and just looked around. To the east, I could hear the sound of a few automobiles in the distances on R.N. 74 and a train that ran along the S.N.C.F. Paris-Lyon railroad tracks. I think I heard an occasional bird whistle. Other than that, nothing was happening.

I looked around some more. I looked at the vineyard. Nothing was happening. No Bacchus-like spirit was divinely dropping bottles of 1995 Romanée-Conti in my lap. I still wasn’t able to think of anything special that I could take away with me to commemorate this lucky day of seeing this vineyard. I suppose I could have taken a stone from the soil with me, but I didn’t feel right about that. I couldn’t help supposing what if every wine pilgrim decided to do that. This was expensive soil.

I also was feeling a little paranoid. With as much money as these estates were raking in from their wine, there was no telling if they had some sort of sophisticated hidden surveillance system. I could just imagine that, as soon as went for a stone, 20 French swat guys would have me surrounded. Then I an annoyed and condescending voice would say in clear English, “Hey, Monsieur Bonehead. Put down our stone and slowly back away from the vines.” I didn’t need that. So I decided to just sit there on the wall of La Romanée-Conti and chill for a few minutes. I was all by myself surrounded by the great vineyards of Vosne-Romanée and sitting at the edge of the most famous one. After about five minutes, I felt more stupid than Linus while waiting for the Great Pumpkin. It was time to go back to Beaune. I gave up trying to think of what special thing I could take away with me from this venerable spot. I guess I’ll just have to go on hoping that someday I’ll uncork a bottle of Romanée-Conti. I got in my car and drove off. It was midnight.