“A bird of beautiful plumage taking pleasure and exulting in its wings.” — British poet Sacheverell Sitwell’s description of Margot Fonteyn.

Ballet, throughout its 500-year history, has experienced several golden eras. Its popularity peaked during different periods due to its fashionableness among European royal courts, new productions based on well-known fables and timeless music of a maestro composer, or the performances of a star ballet dancer. When it was because of a performer, it is possible that audiences were witnessing a rare form of talent which not only required the physical capacity that is demanded of world-class athletes, but also the stage presence and skills to the degree that has only been achieved by the world’s greatest thespians. One of these gifted performers was Margot Fonteyn and she lived a life of epic proportions.

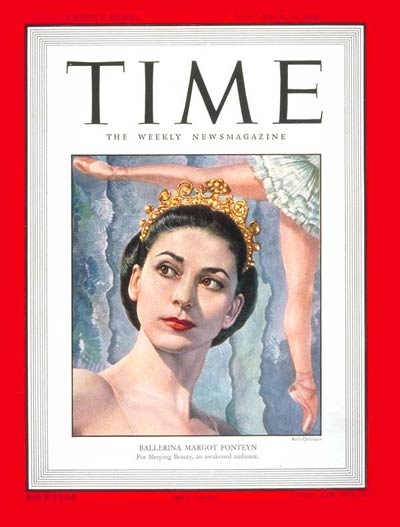

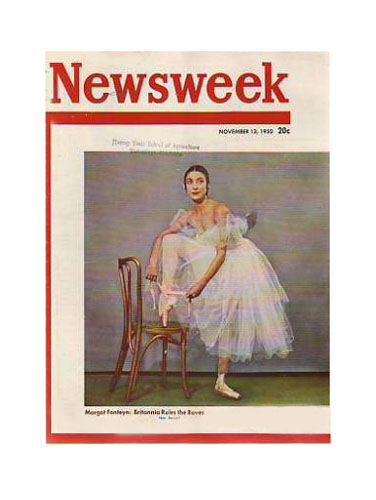

Last month marked the 100th birthday (May 18, 1919) of Dame Margot Fonteyn, the English ballerina who was the star of the Royal Ballet for four decades. She played a key role in establishing Great Britain as a leading force in 20th century ballet as well as helping to broaden the popularity of classical ballet. Her particular beauty, personality, dedication, endurance, and loyalty contributed to her legendary accomplishments and sustainability. She was one of the last great dancers of the last great era of ballet.

“She has a muscular awareness of the phrase which automatically translates music into movement. But beyond this, there is a feeling for choreographic form that gives shape and substance to the composition of what she is dancing, to a degree that one has never seen equaled in the ballet.” — John Martin, New York Times dance critic.

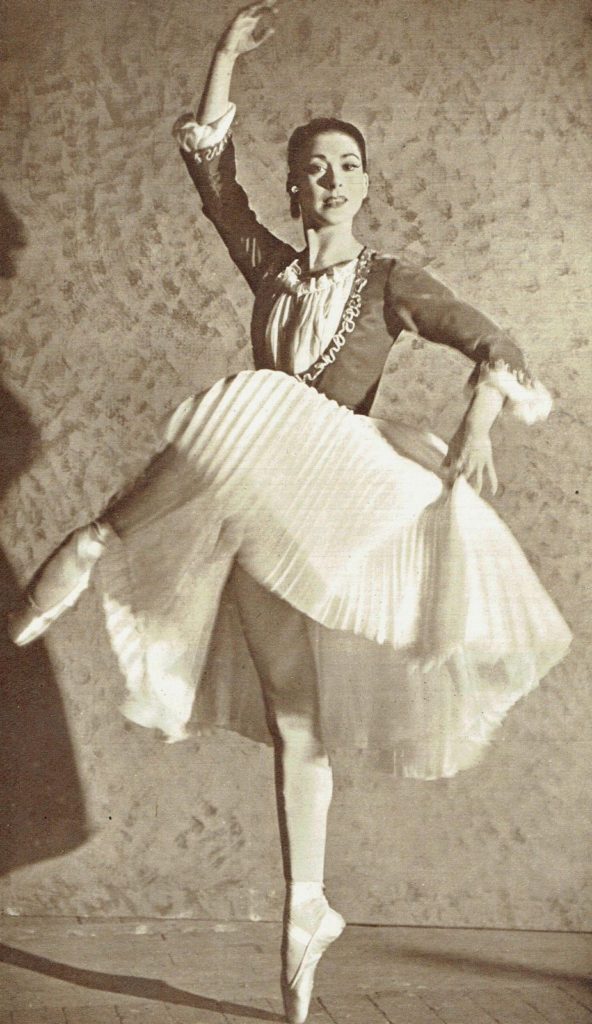

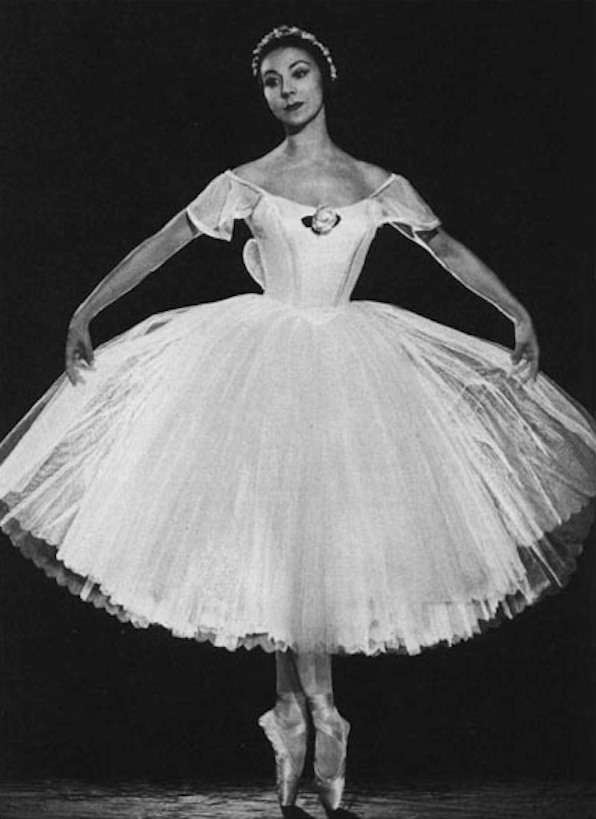

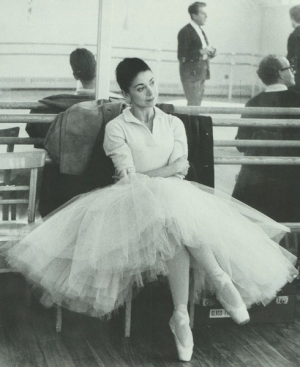

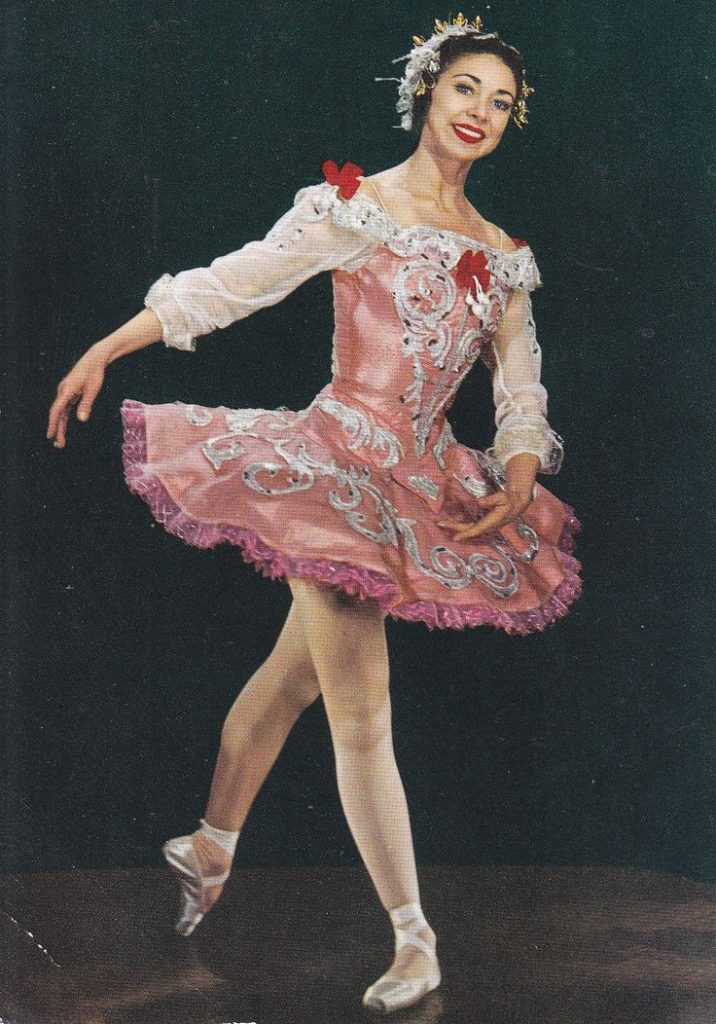

The dance style that Fonteyn developed was the definition of English classical ballet: precise and controlled. She did not possess a natural muscular strength, yet she was considered to have proportions that were perfect for ballet. She had a delicate neck that sat upon her strong straight back. Her back served as the foundation along with her elegant limbs working together to maintain her on pointe balances in a still position. Her bright captivating smile, dark brown eyes, jet black hair, and exotic olive skin gave her a presence that commanded audiences’ attention on her. She conveyed her inner beauty through her personality which displayed her joy, modesty, humility, willpower, and warmth. She brought her audiences into the story that she was telling through dance.

In addition to her physical attributes, she developed skills that enhanced her ability to bring her roles on stage to life. She has often been described as being both a musical and lyrical dancer meaning she was able to understand and feel the music and create the physical movement that both expressed the mood and tone of the musical composition as well as told the story of the production. She blended her refinement with an understated passion. Her technique was genuine. She executed each step with intensity but without force or exaggeration. She was an effective stage actress.

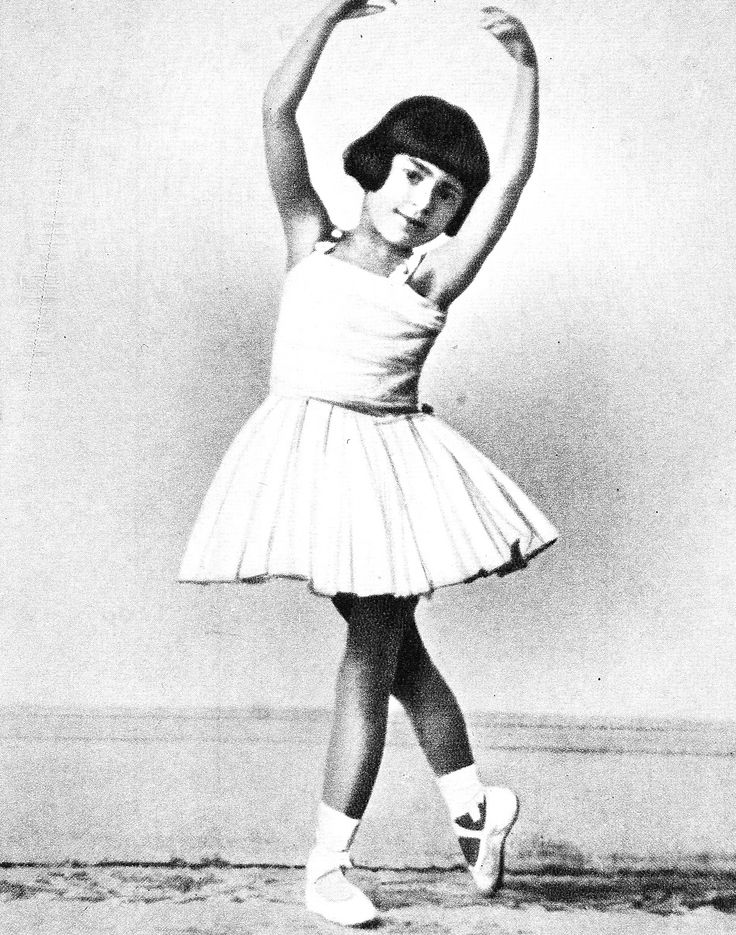

Fonteyn was born Margaret “Peggy” Evelyn Hookham in Reigate, Surrey, a town southwest of London to a lower middle-class family. Her father, Felix, was British and her mother, Hilda, was Irish-Brazilian. Hilda, who would be one of Margot’s closest advisors throughout her career, began taking her to ballet classes in Ealing, London at the age of four and closely watched her daughter’s development over the next ten years. Due to Felix’s job as a mechanical engineer with an international company, the Hookhams moved from London to Louisville, Kentucky, to Seattle, Washington, and eventually located in China where she was taught by a Russian émigré who had performed with the Imperial Ballet in St. Petersburg. By the time Margot was fourteen, Hilda recognized that she was showing some talent that was worth pursuing back in London.

“From an early age I accepted dancing classes as part of my life.” – Margot Fonteyn

Margot’s arrival back in London in 1932 could not have been timed more perfectly. Not long after she began ballet classes in London, Dame Ninette de Valois discovered her and took the young dancer under her wing. De Valois was a former dancer herself and an alumnus of the most influential ballet company of the 20th century, the Ballets Russes. She was the creator in 1931 of what was eventually to become the Royal Ballet (initially called the Vic-Wells Ballet and later changed to the Sadler’s Wells Ballet before receiving its charter after World War II as the Royal Ballet with its home at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden). She immediately spotted the raw talent that Margot possessed, yet recognized her lack of disciplined ballet training. With rigorous tutorage from choreographer, Sir Frederick Ashton, Margot became one of the lead dancers of the company.

Ninette de Valois

Frederick Ashton

Robert Helpmann

The efforts of de Valois, Ashton, and Fonteyn along with musical director, Constant Lambert, and her fellow dancers, like Sir Robert Helpmann, Michael Somes, and Moira Shearer, created the English style of ballet. At the time, there were only four countries with a history and tradition in classical ballet: Italy, France, Russia, and Denmark. Each country developed its own distinct ballet style and method of training dancers. The English style combined all four styles with characteristic British refinement and control. The focus was on the details of each movement to express the story and music. The company was just coming into its stride when Great Britain entered World War II. But this turned out to be an opportunity as they performed nightly for the troops and British audiences in need of a diversion from the war. Margot and the rest of the company would be cherished for their patriotism and bravery in performing during the blitz as well as performing near dangerous war zones on the Continent throughout the war.

Moira Shearer and Margot Fonteyn

Violetta Elvin, Ninette de Valois, and Margot Fonteyn

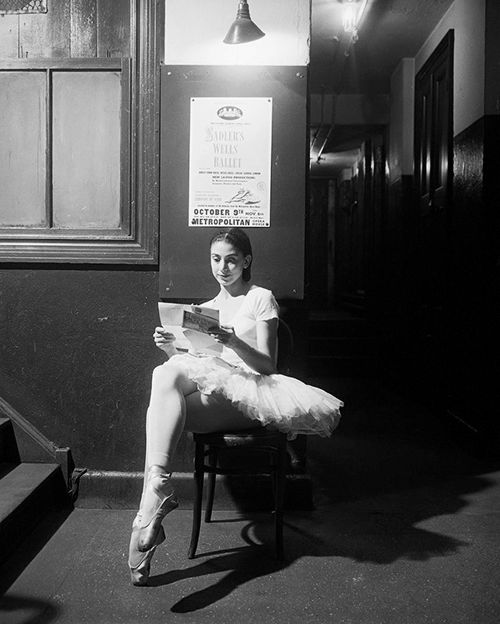

Fonteyn’s most famous roles were Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty, Odette/Odile in Swan Lake, and the title roles in Cinderella, Romeo and Juliet, Ondine, Giselle, Daphis and Chlöe, The Firebird, and Marguerite and Armand. While she said that her favorite role was Ondine, she is most praised for Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty. Two of the key performances of the role took place in 1946 when she first performed the ballet at the Royal Opera House with the royal family in attendance, and in 1949 when Sadler’s Wells Ballet kicked off their first American tour at the old Metropolitan Opera House in New York. The American audiences were primed for live ballet with the success of the movie The Red Shoes (1948) which starred her two fellow performers, Shearer and Helpmann. When Fonteyn made her first appearance on the New York stage, the audience responded with an explosive ovation. At the end of the performance, curtain calls went on for thirty minutes. She became an overnight international sensation. She would be the most adored ballerina for the next two decades.

Aurora

Odette

Ondine

“I thought, it would be like mutton dancing with lamb.” – Margot Fonteyn with initial reservations of dancing at 42 years old with Nureyev who was twenty years younger than her.

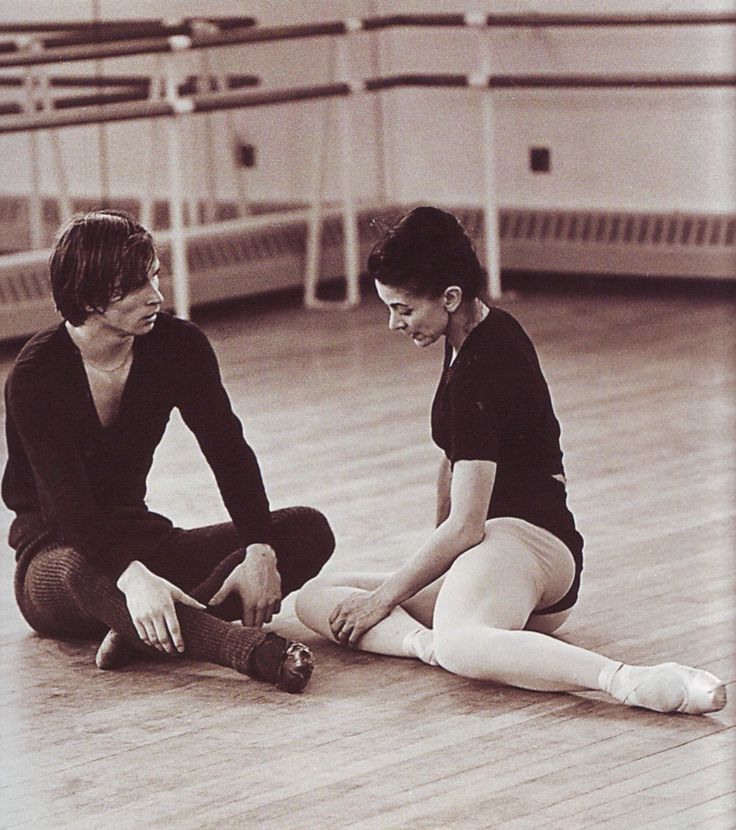

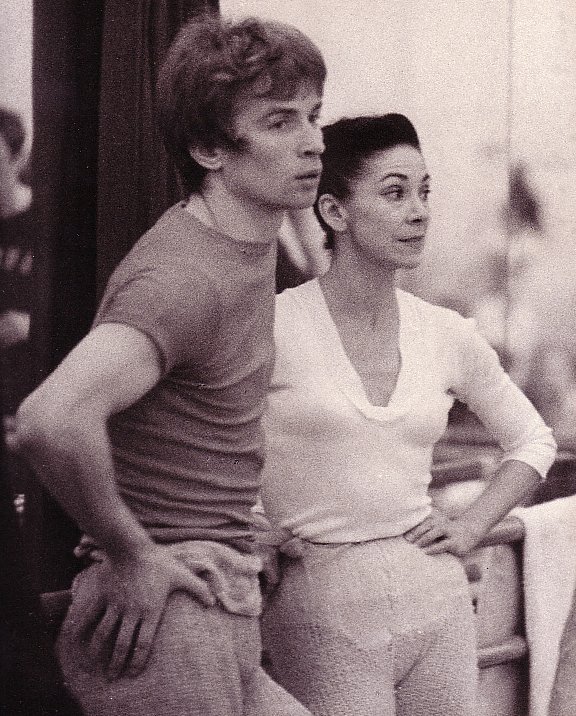

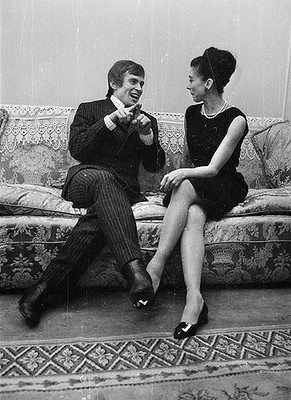

Throughout the 1950s, Margot continued to dance with the Royal Ballet and meet a demanding additional schedule of appearing with other ballet companies across the globe. As the 1950s closed, Margot was approaching forty-years old and thinking about retirement. As an international star, she was doing more special appearances with other ballet companies and less with the Royal Ballet. While she was performing in 1961 with the Royal Ballet at the Kirov Theater in St. Petersburg, word spread about a young star of the Kirov Ballet who had just defected in Paris while the Soviet company was on tour. It turned out to be Rudolf Nureyev. When de Valois found out about his defection, she invited him to join the Royal Ballet which he accepted. She also encouraged Margot to partner with him. After a bit of reluctance on her part mainly because of the twenty year age difference, Margot agreed.

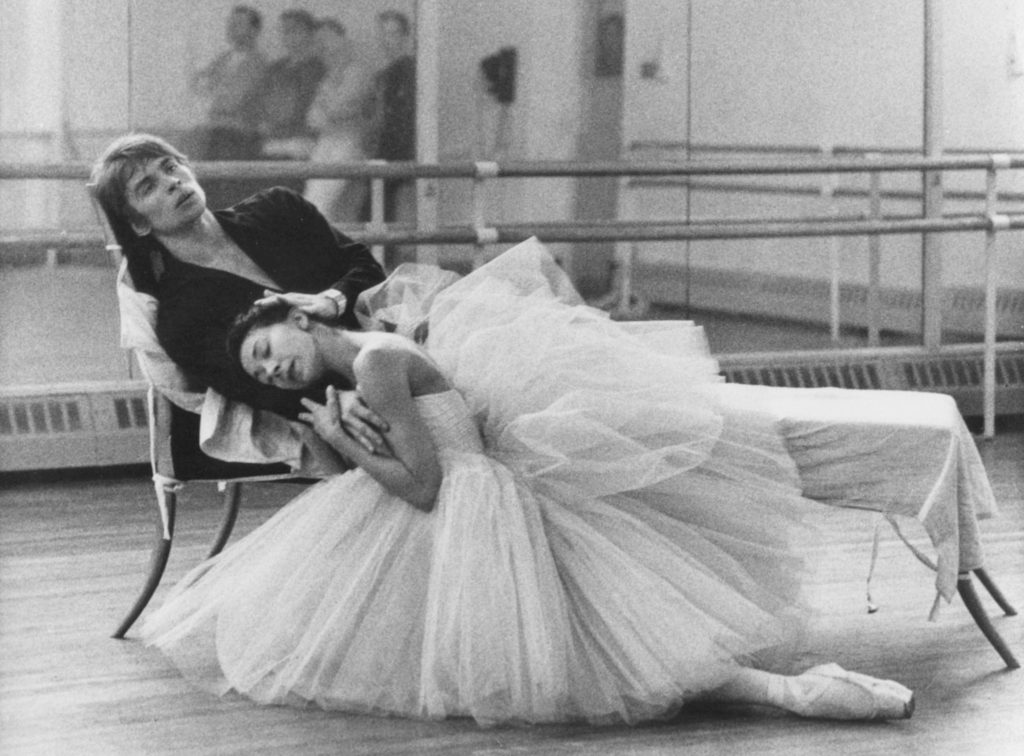

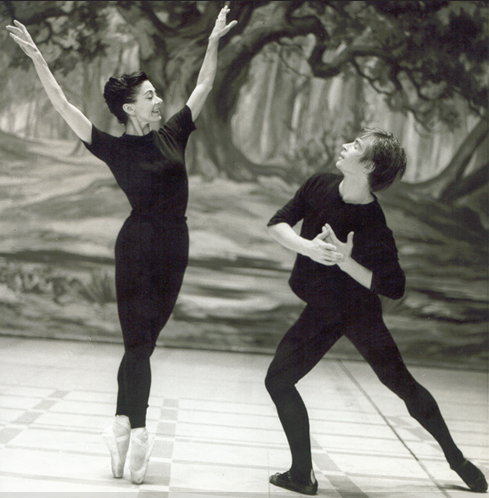

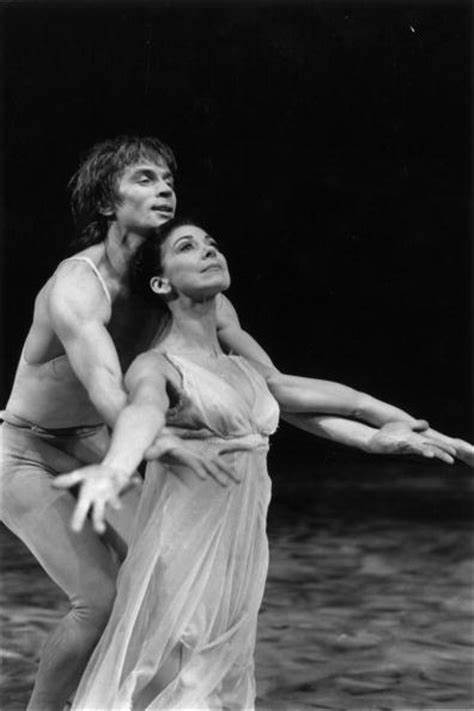

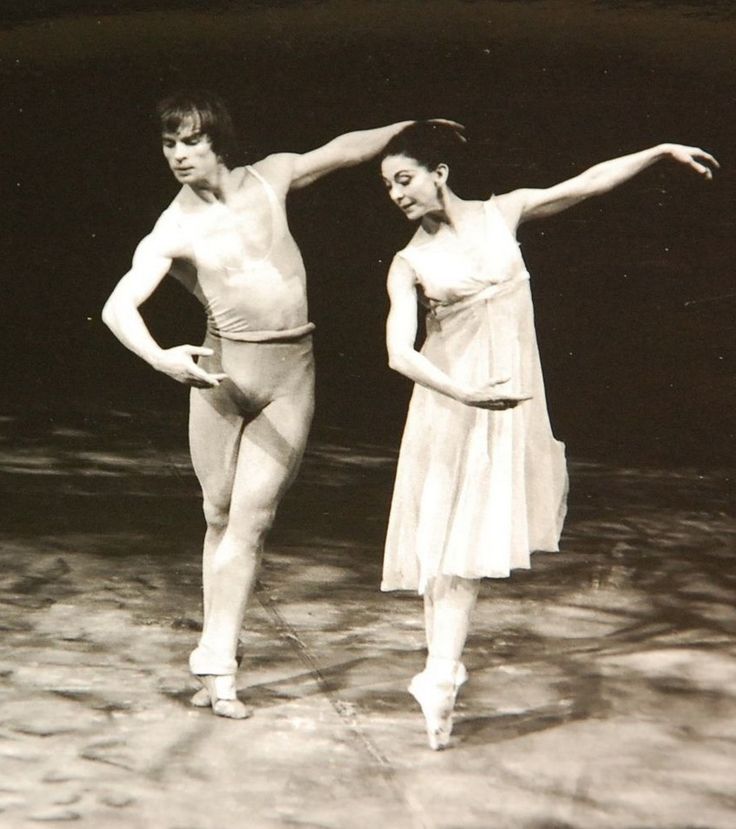

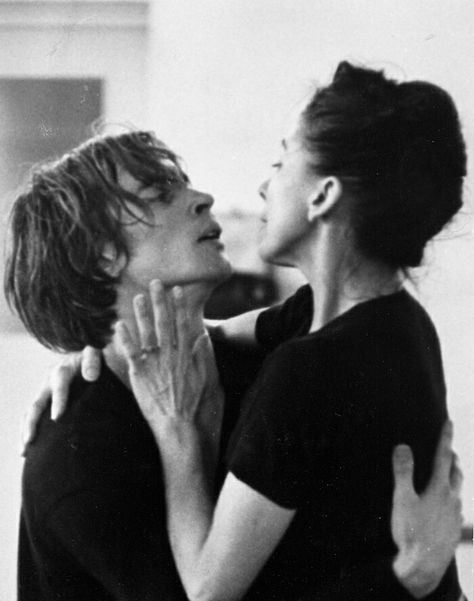

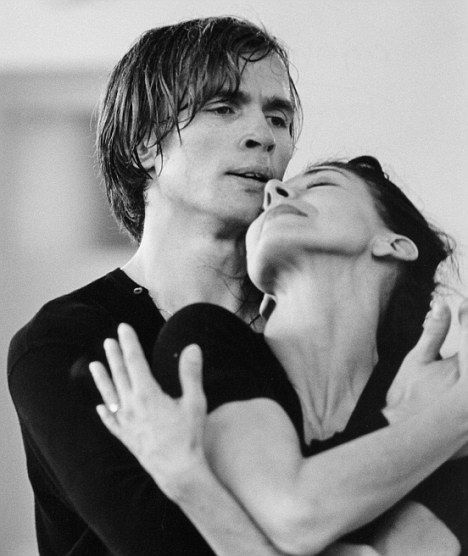

“Something quite special happens when we dance together. It’s odd because it’s nothing we discussed or worked on, yet there in the photos both heads will be tilted to exactly the same angle, both in perfect geometric relationship to each other.” — Margot Fonteyn commenting on dancing with Rudolf Nureyev

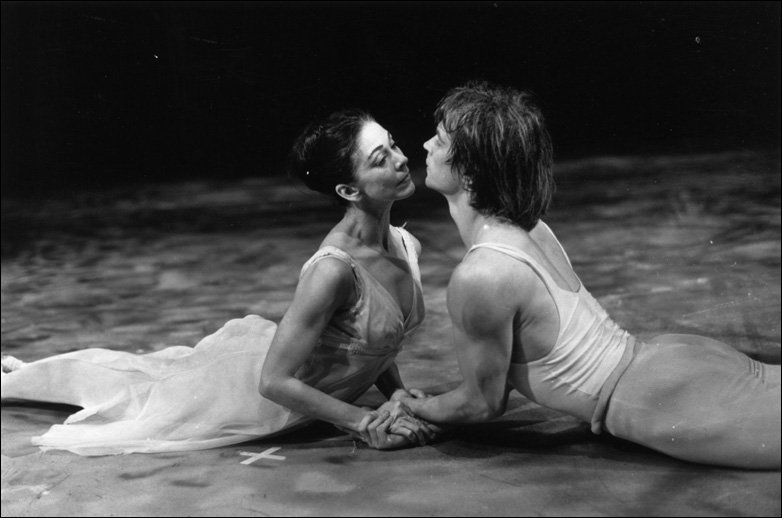

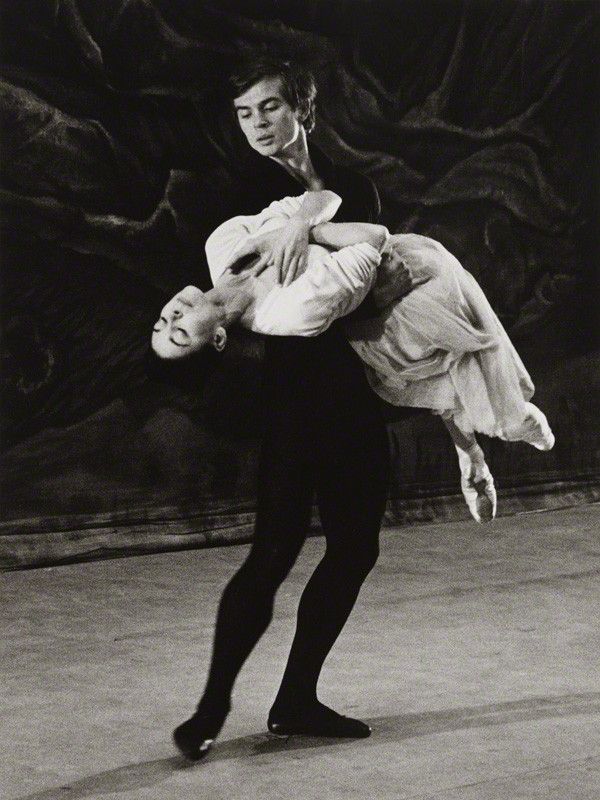

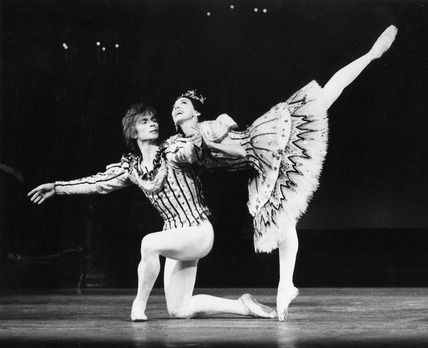

On February 21, 1962, they debuted their first partnership together in London performing Giselle. The enthusiastic audience applauded for fifteen minutes and 20 curtain calls. Their partnership lasted for the next seventeen years. They dazzled the world with their show stopping performances. It has been said that the source of their magic together was how their different approaches and mutual respect forced them to bring out the best in each other. They were the most sought out ticket in ballet. Some of their most notable performances were Les Sylphides, Marguerite and Armand, Romeo and Juliet, and Swan Lake.

“For me, she represents eternal youth.” — Rudolf Nureyev about Margot Fonteyn

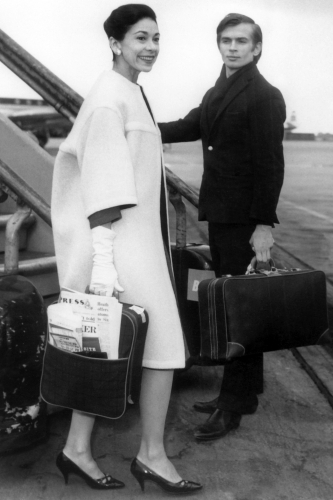

Margot had an intriguing personal life that made international headlines and often baffled those close to her. Having such a busy schedule with performances around the world certainly made things difficult on her having a personal life. She had her share of brief love affairs, but one relationship in particular lasted. She met Roberto “Tito” Arias just before World War II when the company performed at the University of Cambridge. Tito was a law student from Panama whose father was a former President of Panama. They spent much of their time together when the ballet company made these visits. For Margot their common Latin roots was part of the attraction. Once the war started, they lost touch with each other. However in 1953, he reconnected with her by visiting her in various cities around the world where she was performing. By this time, he was a maritime lawyer, a United Nations diplomat, owned his own shipping company, was married with three children, and involved in Panamanian politics. Within a short span of time, he divorced his wife, married Margot, and became the Panamanian Ambassador to the Court of St. James in London. It appeared that the two were on their way to living a charmed life.

Their marriage had its highs and lows. The highs involved jet setting around the world, sailing the Mediterranean with the likes of Aristotle Onassis and Winston Churchill, socializing with other dignitaries and celebrities, and hosting parties and dinners in London – all while she was continuing to be the premier ballerina for the Royal Ballet. Margot also became a fashion icon with couturiers Christian Dior and then Yves Saint Laurent designing her wardrobe. The lows revolved around the fact that Tito was not a reliable nor faithful husband. He was known for having affairs throughout their marriage and at times appeared to have little respect or interest for Margot’s demanding schedule.

Fonteyn with Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip

Fonteyn with Robert F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

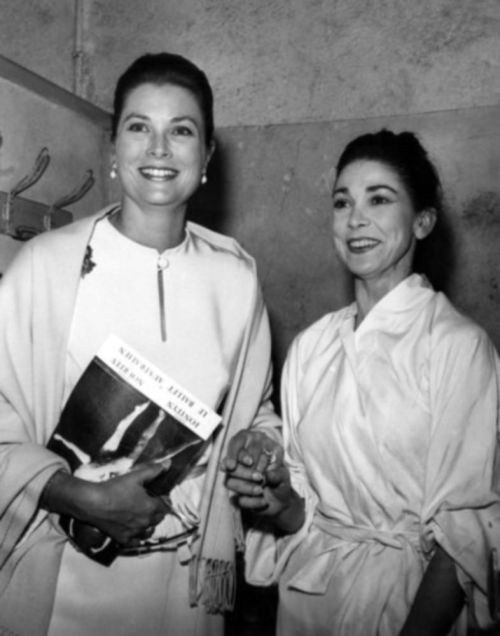

Grace Kelly (Princess of Monaco) with Fonteyn

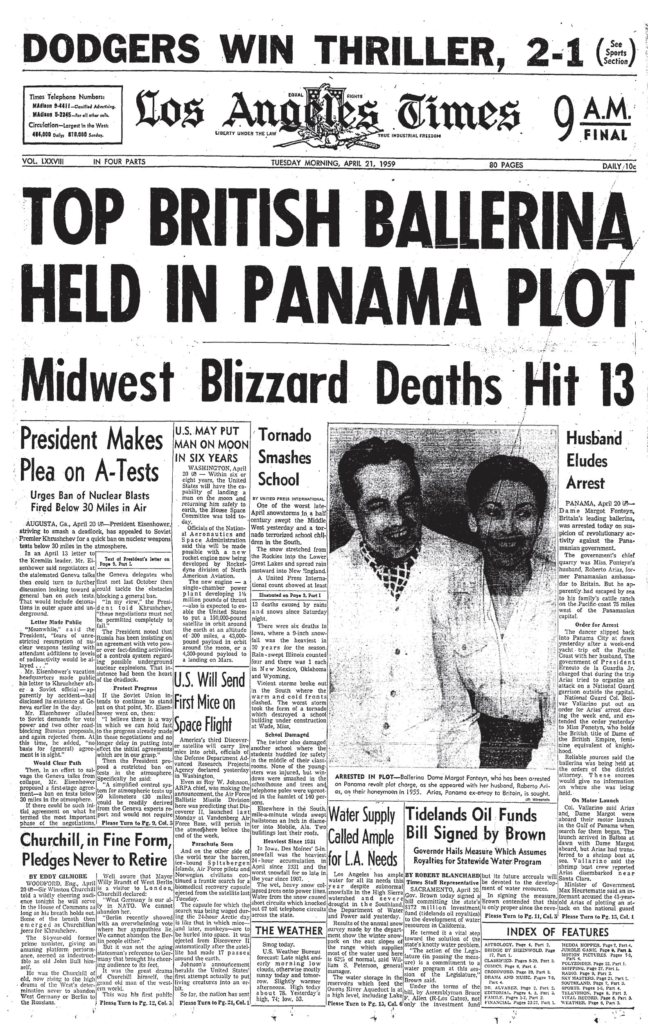

They had bizarre adventures. In January of 1959, days after Fidel Castro came into power, Tito and Margot flew to Havana to meet him. It is believed that the two men discussed Castro’s support for Tito’s plan to carry out a coup d’état against Panamanian President Ernesto de la Guardia. Tito attempted his coup that April but failed. Margot was actively involved by acting as a decoy while Tito smuggled guns to his fellow rebels. She was arrested and questioned, but British authorities intervened and were able to get her out of the country to New York by way of Miami, and then out of the U.S. back to London. She was not able to speak to Tito for six days and was not able to reunite with him for two months. Dodging bullets, he was able to escape Panama and meet her in Brazil. Through it all, Margot maintained her grace and composure when swarmed by the paparazzi. Surprisingly, the incident quickly blew over and received little attention as time went on.

Their topsy-turvy marriage began to fall apart after the coup. Tito’s shipping company went bankrupt and his family’s influence and wealth declined. Margot found the international touring lonely especially with Tito reverting back to his carefree lifestyle. He was also busy returning to politics in Panama after a new regime came into power. The unstable and impracticable situation became so unfulfilling and frustrating for Margot that she began making plans to divorce him. However, a tragic twist of fate in 1964 changed those plans. While she was performing in England, an assassination attempt was made on Tito in Panama when a political associate shot him five times. He miraculously survived the attack, but remained completely paralyzed for the rest of his life. Margot remained with him the whole time and was devoted to his well-being until his death in 1989. Paying for his expensive healthcare was a major reason why she continued to perform in the 1960s and 1970s.

Margot performed less frequently in the 1980s. Her extended career had taken a toll on her body, especially on her feet as her arthritis grew more intense. She was still occasionally celebrated by her peers. For instance, the Royal Ballet gave her the rare distinction of prima ballerina assoluta. Away from the stage, she spent more time in Panama with Tito, wrote a few books including her autobiography, taught a few master classes, made special appearances, and produced a few documentaries on dance. She was also appointed chancellor of Durham University. She and Tito also owned a cattle ranch in Panama that they operated for her remaining life. She contracted ovarian cancer in the late 1980s that she battled for two and a half years until her death in 1991 at the age of 71. Tito’s poor management of the ranch left her in such bad financial shape that she was first buried in Panama in a modest grave. Her remains were appropriately later relocated with Tito at the national cemetery. With the previous deaths of Ashton and Helpmann and the subsequent death of Nureyev, a glorious era of ballet had passed.

The world of ballet today is very different from Margot’s time. There is no longer a distinction in national styles of classic ballet. Dancers today are expected to perform them all as well as other ballet styles. Ballet is no longer at the center of the performing arts for most metropolitan cities. Ballet companies are struggling to attract donors and audiences which consist disproportionately of dancers and ex-dancers. Training today focuses more on technique and athleticism at the expense of developing artistry and emotion. Formalized competition is stressed more than developing a dancer’s stage presence and personality. Dancers today lack a humility toward the discipline and prestige of ballet as well as an appreciation of its history and those who proceeded them. Ballet is just not as interesting as it was in the past. The connection with audiences is lacking. Many in the ballet world begrudgingly know this and are trying to bring the popularity of ballet back. Nevertheless, there is great talent and intense passion in today’s ballet world. However, with today’s cultural choices, it’s a long road to bringing ballet back to the glory it once had. Perhaps reviewing what Margot Fonteyn and the Royal Ballet achieved might be a good place to start.

“My attitude has never changed. I cannot imagine feeling lackadaisical about a performance. I treat each encounter as a matter of life and death. The one important thing I have learned over the years is the difference between taking one’s work seriously and taking one’s self seriously. The first is imperative and the second is disastrous.” Margot Fonteyn summing up her career.

*************

FONTEYN AND NUREYEV