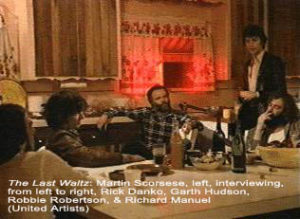

As shown in the Martin Scorsese 1978 film, The Last Waltz:

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame members of the Band recount to Scorsese their story of meeting Sonny Boy Williamson in 1965, when the Band was known then as Levon and the Hawks. The group was traveling in the South for various gigs.

Robbie Robertson: Levon’s hometown. It’s near West Helena, [Arkansas]. One time [in 1965] we were there for some reason or another, and we decided we were going to look up one of the legends of that town which was Sonny Boy Williamson.

Robbie Robertson: Levon’s hometown. It’s near West Helena, [Arkansas]. One time [in 1965] we were there for some reason or another, and we decided we were going to look up one of the legends of that town which was Sonny Boy Williamson.

Richard Manuel: In my opinion, he’s the best harp player – that’s like harmonica, blues harmonica – that I’ve ever heard.

Robertson: He’s the big daddy of them. And he took us to a friend of his, a woman’s place, who served food and corn liquor . . .

Rick Danko: . . . in a southern booze can.

Robertson: And he would sit there and he was playing for us. And we were getting drunk and trying to figure out where we were . . .

Danko: . . . we were wiped out.

Robertson: And he was spitting in a can. I thought he was dipping snuff. I thought maybe he had something in his lip. And he kept spitting in this can and playing, and we kept getting drunker. Finally, I looked over in the can and I realized it was blood. He was getting pretty tired and pretty drunk by then. And we made big plans for the future and all kinds of things we were going to do. And it was tremendous. A great night. A couple of months later, we got a letter from his manager, or whoever it was, saying that he had passed away.

Here is another interview with Robbie Robertson where he tell more about the Band’s meeting with Sonny Boy Williamson:

Here is another interview with Robbie Robertson where he tell more about the Band’s meeting with Sonny Boy Williamson:

* * * * *

Wait a minute! Sonny Boy Williamson? The big daddy of harp players? Helena, Arkansas? I grew up just two hours from Helena! I was born and raised in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, one of the towns on the western fringe of the Mississippi River Delta. You would think I would have found the time to learn about Sonny Boy during all my years in Arkansas. As it were, instead of being in the Deep South while having my first lesson in appreciating the blues, I was clear across the Atlantic Ocean in the deep hills of Tuscany. Here I was in the cradle of the Renaissance, a place that produced individuals whose work had tremendous influence throughout the world, when I finally began to realize and pay attention to the fact that I was from a part of the world that was responsible for a worldwide cultural and creative explosion of its own. Although at first glance, the Delta is not recognized as one of the premier cultural havens of the world (compared to Tuscany at any rate), I realized that the Delta, in fact, has much to offer as the birthplace of blues and its progeny, rock and roll. It was the home of journeymen like Charley Patton, Son House, Robert Johnson, Elmore James, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King, and Sonny Boy Williamson, who were playing “the music of the devil” in the 1920s through the 1950s. These were the godfathers to younger stars of the Delta like Carl Perkins, Ike Turner, Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis Presley, and others who ran with this sound and smacked the world over the head with the force of rock and roll.

To my chagrin, I finally got around to seeing The Last Waltz, the historical rock documentary film on the Band’s 1976 swansong performance at the Winterland Theater in San Francisco. I was aware of the film since its release, but I never made the time to watch it until just a few years ago when I found the DVD for sale in 2003 in a Blockbuster video store in Siena. Little did I realize that I was about to watch a film that would have a profound effect on me. From Rick Danko’s bass riff at the start of Marvin Gaye’s Don’t Do It, I was hooked. The limited facts that I knew about the Band before seeing this film were that the drummer, Levon Helm, was from Arkansas and their two biggest hits, The Weight and The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down. Robbie Robertson was an intriguing storyteller and had an authoritative presence on stage as the group’s guitarist. Levon made some interesting remarks about the importance of the music from the Delta. It was a delightful discovery to learn that Ronnie Hawkins, the man who was responsible for bringing the five members of the Band together in the early 1960s when they were known as Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks, was also from Arkansas.

The Band was heavily influenced by the earlier music that came from the South: blues, country, and gospel. It was interesting to see how they took those influences and created their own interpretations. They had a high regard for music history and the musicians who created the roots of a sound in the first half of the twentieth century. I was completely open to what these guys had to offer with their music and listened intently to their thoughts and opinions on music. By the time the film came to the discussion on Sonny Boy Williamson, I felt an immediate enthusiasm to learn all that I could about this legendary musician. The fun thing about this mission was that part of the research was to take me to my home and I was going to learn one of the stories that made the part of the world where I am from a special place.

The Adventure Begins

Baaaaaaby. (Whaaaaawaawaawaa-wawoowoa!)

Baaaaaaby. (Whaaaaawaawaawaa-wawoowoa!)

I’m gonna bring it on home to you.

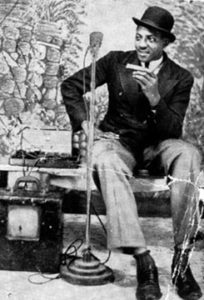

I started this journey by reading all I could on Sonny Boy and listening to several of his recorded songs. From the way the Band told the story in the film, I was expecting to read about some sweet old black man. Friendly. Modest. Soft spoken. As I discovered, he was anything but that. This man was the quintessential hard-drinking, hard-loving, and hard-living traveling Delta blues virtuoso of the segregation years. He liked his liquor, his women, his gambling and his music and he wouldn’t put up with anyone interfering with any of his vices. He was hot-tempered and easily could be provoked into a fight. B.B. King, who knew Sonny Boy since their early days working in West Memphis, Arkansas, said that he often had a don’t-bother-me-with-no-bullshit look on his face. He was a loner and often kept to himself. He trusted no one. His personal relationships, including two marriages, often suffered from his born-under-a-wandering-star nature. He would often go off to places without telling anyone.

He had an imposing presence. He was six feet, two inches tall. He had large hands and feet. He slit open the sides of his shoes for comfort. Although he was not one to reveal too much about himself, his face expressed a life of hard living. His bloodshot eyes were shaded under protruding eyelids and supported with heavy bags. His expressions seemed to convey a contradictory combination of charm and intimidation.

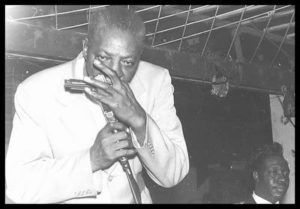

He seemed to be at his best when he was playing his blues. As time went on, word spread from the small Delta towns to the whole world about his remarkable talent. He defined his own style. He combined humor and autobiographical lyrics with lonesome and erotic harp riffs. His voice was husky; sometimes it was a whisper. His improvisations with the Marine Band harp (and sometimes with the lower-pitched twelve-hole diatonic harp such as on Bye Bye Bird) were brilliant. He usually played the harp unamplified. He would use his cupped hands, palm in palm, to assist in his choked harp style. His hallmark was creating smooth rhythms separated by sharp, simple melodic riffs. He was the master of phrasing and had an impeccable sense of time. Sonny Boy was an extraordinary showman. Sometimes he would play with the whole harmonica in his mouth.

The Early Years

I done bought my ticket. I got my load. (Whrwhrwhrwhr-whrwhrwhrrrr)

Conductor done hollered, “All aboard!” (Whrwhrwhrwhr-whrwhrrrr)

Sonny Boy was born Aleck Ford in Glendora, Mississippi, which is about 40 miles south of Clarksdale. Various dates between 1894 and 1912 have been given for his date of birth. He was the last of the twenty-one children to whom his mother, Millie Ford, gave birth. Not much is known about his father. The father figure in his family was his stepfather, Jim Miller (although he is identified on Sonny Boy’s death certificate as Jim Williamson). Aleck was given the nickname “Rice” at an early age supposedly due to his love for milk and rice. As he grew up, his contemporaries knew him as Rice Miller.

Sonny Boy was born Aleck Ford in Glendora, Mississippi, which is about 40 miles south of Clarksdale. Various dates between 1894 and 1912 have been given for his date of birth. He was the last of the twenty-one children to whom his mother, Millie Ford, gave birth. Not much is known about his father. The father figure in his family was his stepfather, Jim Miller (although he is identified on Sonny Boy’s death certificate as Jim Williamson). Aleck was given the nickname “Rice” at an early age supposedly due to his love for milk and rice. As he grew up, his contemporaries knew him as Rice Miller.

It is believed that he learned to play harmonica at an early age. Unlike other blues legends of that time, his family did not discourage him from playing the harmonica nor pressured him to find more legitimate work. By the time he reached majority, he was still living with his parents until his stepfather kicked him out of the house. Through the 1920s and 30s, Rice was a rambling Delta blues man. He played the juke joints in the upper Delta. It was a rough and tumble world of vulgar street language, smoky and stale air, and plenty of gambling, booze, and women. The sounds and beats of a raw style of music got into everyone’s blood. Often a fight would break out in this boiling and contentious atmosphere.

Sometimes the fights turned deadly. And Miller would sometimes be right in the middle of all this action. It was during this stage that he met up with Robert Johnson with whom he played and traveled until Johnson’s death in 1938. Rice was later quoted as saying that he was with Johnson the night he died. In fact, he claimed that Johnson died in his arms.

King Biscuit Time

Take my seat and ride way back, (Whrwhrwhrwhr-whrwhrrrr)

And watch this train move down the track. (Whrwhrwhrwhr-whrwhrrrr)

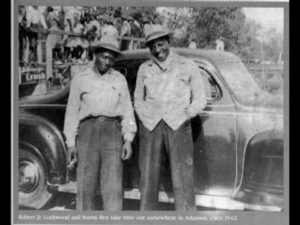

The year before Johnson died, Miller began playing with a guitarist who he would collaborate with for three decades. His name was Robert Jr. Lockwood. After his parents separated, Robert’s mother began seeing Robert Johnson. Lockwood was heavily influenced by Johnson and honored him for teaching him how to play the guitar by putting “Jr.” after his first name and even referred to Johnson as his stepfather. Lockwood accomplished much in his career and is considered one of the most influential guitar players of all time.

Probably the most important collaboration of Miller and Lockwood was their performances on the King Biscuit Time radio show in Helena, Arkansas, between 1941 and 1944. Traveling in all the juke joints in Mississippi and Arkansas, they were aware of other blues musicians who were featured on local radio shows which allowed them to promote their live performances. Miller and Lockwood saw their chance to take advantage of this medium in 1941 when Sam Anderson started Helena’s first radio station, KFFA. Miller and Lockwood approached him about playing on the station and plugging their gigs on the air. Anderson agreed. Soon Max Moore, the owner of the Interstate Grocery Company got involved as a sponsor to promote his product, King Biscuit Flour. On November 19, 1941, Miller and Lockwood made their KFFA (1250 AM) King Biscuit Time radio debut at 12:00pm.

Clang! “It’s King Biscuit Time, so pass the biscuits!” the announcer said. “Light as air. White as snow. Yes, friends, that’s King Biscuit Flour, the perfect flour for all your needs.” Miller and Lockwood would immediately launch into the show’s theme that was a lyrical revision of Miller’s Good Evening Everybody.

It was around this time that Rice Miller adopted the name, Sonny Boy Williamson, which caused much confusion and resentment among other blues musicians. The problem stemmed from the fact that there already was a renowned harp player named Sonny Boy Williamson. John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson from Tennessee was performing in Chicago around this time. John Lee was younger than Miller, but recorded songs first. Why Miller insisted on this name was never made clear. However, Miller always insisted that he was the original Sonny Boy Williamson despite some opinions to the contrary. Miller claimed that John Lee had stolen the name from him when he recorded Good Morning Little School Girl for Bluebird in 1937. There is a story that in 1942 John Lee Williamson came down to the South to confront Miller on the issue.

According to Lockwood, the physically imposing Miller chased the small-framed John Lee out of town. Miller’s talent seemed to win him the argument even though John Lee was very popular. Several contemporary musicians, like Lockwood and Sonny Boy’s Chess Records producer, bassist and frequent songwriter, Willie Dixon, believed that Miller was the better musician and better entertainer. Another fact that helped Miller to continue use of the name was that John Lee’s life was cut short when he was stabbed and killed in Chicago in 1948. The historians have tried to resolve this confusion by naming John Lee – Sonny Boy Williamson I and Rice Miller – Sonny Boy Williamson II.

According to Lockwood, the physically imposing Miller chased the small-framed John Lee out of town. Miller’s talent seemed to win him the argument even though John Lee was very popular. Several contemporary musicians, like Lockwood and Sonny Boy’s Chess Records producer, bassist and frequent songwriter, Willie Dixon, believed that Miller was the better musician and better entertainer. Another fact that helped Miller to continue use of the name was that John Lee’s life was cut short when he was stabbed and killed in Chicago in 1948. The historians have tried to resolve this confusion by naming John Lee – Sonny Boy Williamson I and Rice Miller – Sonny Boy Williamson II.

The radio show with its 35-mile range was an immediate success. The show’s spot ran for fifteen minutes each weekday. On Saturdays, the King Biscuit Entertainers would visit grocery stores throughout the northern Mississippi Delta. Sonny Boy and Robert Jr. expanded their band to include guitarist Joe Willie “Pinetop” Wilkins, drummer James “Peck” Curtis, and pianist Robert “Dudlow” Taylor. Houston Stackhouse would fill in when needed. The show went on to become a long-running platform for Rice “Sonny Boy Williamson” Miller’s popularity. By 1944, the Interstate Grocery Company introduced a new product called Sonny Boy Corn Meal with Sonny Boy’s photo on the packaging.

In 1944, Sonny Boy felt the itch to travel again and quit doing the show on a regular basis, but would always return to the show when he was in town. Lockwood would leave the next year, but the show continued and continues daily with the show’s veteran announcer, “Sunshine” Sonny Payne. For the rest of the 1940s, Sonny Boy traveled and performed with other musicians, like Elmore James, in various towns in Arkansas, Mississippi, and a few other southern states. With his wife Mattie, West Memphis became their home for a short time. In 1949, while working on a radio show in West Memphis, Sonny Boy helped Riley (soon to be B.B.) King obtain his first paid gig.

Sonny Boy Finally Records His Music

Baaaaaaby. (Whaaaaawaawaawaa-wawoowoa!)

Baaaaaaby. (Whaaaaawaawaawaa-wawoowoa!)

I’m gonna bring it on home to you.

The 1950s brought on a major stepping stone for Sonny Boy. After three tough decades as a traveling musician, his music would finally be recorded allowing him to reach a larger audience. He made his first recordings in 1951 when Lillian McMurry of Jackson, Mississippi’s Trumpet Records recorded several of his classics. His first recording session was on January 5, 1951. He recorded Eyesight to the Blind with Pinetop Wilkins, pianist Willie Love and Frock O’Dell on drums. Elmore James joined the group on Robert Johnson’s I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom. These two songs were regional hits for Sonny Boy. Other songs that he recorded at Trumpet were Mighty Long Time, Nine below Zero, Too Close Together, Pontiac Blues, and West Memphis Blues. Over the next five years, Sonny Boy continued to relocate living in Detroit, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and Chicago at different times and meeting up with fellow blues musicians.

The 1950s brought on a major stepping stone for Sonny Boy. After three tough decades as a traveling musician, his music would finally be recorded allowing him to reach a larger audience. He made his first recordings in 1951 when Lillian McMurry of Jackson, Mississippi’s Trumpet Records recorded several of his classics. His first recording session was on January 5, 1951. He recorded Eyesight to the Blind with Pinetop Wilkins, pianist Willie Love and Frock O’Dell on drums. Elmore James joined the group on Robert Johnson’s I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom. These two songs were regional hits for Sonny Boy. Other songs that he recorded at Trumpet were Mighty Long Time, Nine below Zero, Too Close Together, Pontiac Blues, and West Memphis Blues. Over the next five years, Sonny Boy continued to relocate living in Detroit, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and Chicago at different times and meeting up with fellow blues musicians.

In 1955, Williamson began the pinnacle of his recording years when Chess Records in Chicago bought his contract from Trumpet and launched his recording career with their label and through their subsidiary, Checker Records. He would continue to record with Chess until 1964. His first session was with Muddy Waters’ band on August 12, 1955. He recorded Don’t Start Me Talkin’, All My Love in Vain, and Good Evening Everybody. Among the many other songs he would record with other blues legends at Chess were Help Me, Keep It to Yourself, Your Funeral and My Trial, Fattening Frogs for Snakes, Bring It On Home, and Bye Bye Bird. His last session with Chess was in August 1964 with Buddy Guy’s band. The song was Mattie Is My Wife. His eighteen Chicago sessions produced just over 70 tracks.

Sonny Boy Comes Homes To Stay

I think about the goods times I once have had. (Whrwhrwhrwhr-whrwhrrrr)

Soul got happy now, my heart got glad. (Whrwhrwhrwhr-whrwhrrrr)

The 1960s saw the height of Sonny Boy’s fame at a time when blues was experiencing an international resurgence in popularity. In 1962, he was a featured performer at the American Folk Blues Festivals in Europe. Between 1963 and 1965, he made three trips to Europe playing with several other elite bluesmen. He was particularly fond of England and remained there for a while on his last journey to Europe. He was so amused with British formal attire that he had two-tone black and charcoal gray suits made on Savile Row and wore a bowler hat and kid gloves. While in England, he recorded with some young rock and roll musicians who molded their music from the Delta blues sound. Sonny Boy was royalty to these men like Eric Clapton and the Yardbirds, the Animals, Brian Auger and the Trinity, and Jimmy Paige, although supposedly, he did not feel that his style of music meshed with these rockers.

Williamson returned to the Delta for good in 1965. He was a sick man and he knew he did not have much more time left to live. He rented a small apartment off of Walnut Street in Helena. Robert Palmer in his seminal book, Deep Blues, recounts a conversation between Sonny Payne and Sonny Boy shortly after he returned to Helena:

Williamson returned to the Delta for good in 1965. He was a sick man and he knew he did not have much more time left to live. He rented a small apartment off of Walnut Street in Helena. Robert Palmer in his seminal book, Deep Blues, recounts a conversation between Sonny Payne and Sonny Boy shortly after he returned to Helena:

“Sonny Boy, I thought you were having a ball over there in Europe.”

“Yes, sir. I was.”

“Why’d you come back?”

“I just come home to die. I know I’m sick.”

“How do you know you’re going to die?”

“We just like elephants. We knows.”

Palmer also quoted Houston Stackhouse who said Sonny Boy told him, “Well, Stack, I done come home to die now.”

Williamson valued his remaining days. He traveled the region and visited old venues. He fished on the levees and returned to perform on King Biscuit Time. As transcribed in the opening of this article, it was during this time he was sought out by a group of five blossoming musicians, who would later be Bob Dylan’s backup band and then form their own group, the Band, and would make their own mark on music history.

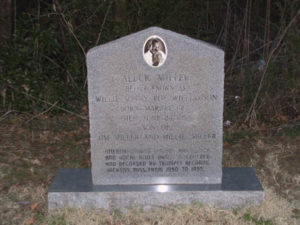

All of Sonny Boy’s hard living caught up with him a month later on May 25 when he died in his sleep in his small apartment in Helena. For his well-attended funeral, his remains were taken back to Tutwiler, Mississippi, where his wife, Mattie, was living. He was buried next to a small church just outside of Tutwiler among the extensive cotton field plains. Lillian McMurry had a headstone placed on his grave in 1980 which read: Aleck Miller, Better Known As Willie “Sonny Boy” Williamson, Born March 12, 1905, Died: June 23, 1965 [incorrect date], Son of Jim Miller and Millie Miller, Internationally Famous Harmonica and Vocal Blues Artist Discovered and Recorded By Trumpet Records, Jackson, Miss. From 1950 to 1955.

All of Sonny Boy’s hard living caught up with him a month later on May 25 when he died in his sleep in his small apartment in Helena. For his well-attended funeral, his remains were taken back to Tutwiler, Mississippi, where his wife, Mattie, was living. He was buried next to a small church just outside of Tutwiler among the extensive cotton field plains. Lillian McMurry had a headstone placed on his grave in 1980 which read: Aleck Miller, Better Known As Willie “Sonny Boy” Williamson, Born March 12, 1905, Died: June 23, 1965 [incorrect date], Son of Jim Miller and Millie Miller, Internationally Famous Harmonica and Vocal Blues Artist Discovered and Recorded By Trumpet Records, Jackson, Miss. From 1950 to 1955.

Visiting Helena

I think about the way you love me too. (Whrwhrwhrwhr-whrwhrrrr)

You can bet your life, I’m coming home to you. (Whrwhrwhrwhr-whrwhrrrr)

One January afternoon in 2004, I drove from Pine Bluff to Helena, which lies on the west bank of the Mississippi River. Helena was once a thriving river port city in its pre-World War II years. After the war, its commercial activity slowly came to an end in the 1960s as trade was taken away by the rail and road freight industries. Helena is now a quiet yet still active southern town. Like many small southern towns, most of the activity of its 6,300 residents has moved away from downtown.

The two main streets in downtown Helena are Cherry Street and Walnut Street, and Elm Street was the main artery between the two. King Biscuit Time was broadcasted in various buildings on Cherry Street. Gist Music Company at the corner of Cherry and Elm was where Sonny Boy bought his harmonicas. The store is still in operation today. They are all gone now, but the juke joints where Sonny Boy, Robert Johnson, and other blues greats played together during Helena’s heyday ran along Walnut Street. The Interstate Grocery Company is no longer a viable entity but the gutted-out shell of the factory monumentally still stands on Walnut Street like a Roman ruin.

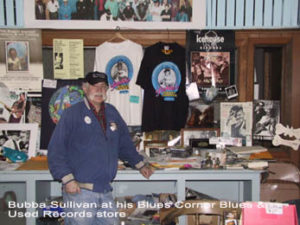

I had made an appointment to meet with Wayne Andrews, the executive director of the Arkansas Blues and Heritage Festival, which until last year was known as the King Biscuit Blues Festival. Wayne also made arrangements for me to meet with one of the Sonny Boy Blues Society’s founding members, Bubba Sullivan, and “Sunshine” Sonny Payne, the legendary announcer himself. I spent a good part of a day with these gentlemen talking about Sonny Boy and Helena’s blues history.

Since the 1980s, thousands of blues fans have come to downtown Helena in October for the King Biscuit Blues Festival. The idea originated when a few residents decided they must do something to preserve the town’s distinguished blues history. They created the Sonny Boy Blues Society (SBBS). Organizing the annual free blues festival is one of their main projects. “People who were lifelong residents,” Andrews said, “believed that this is a great thing for our city to remind people what came from Helena.”

The Society’s efforts have been greatly appreciated by blues fans. In 2003, 85,000 people from all over the world attended Helena’s 19th annual festival. This is the largest ongoing blues festival in the world. In addition to the festival, Helena attracts thousands of blues pilgrims each year. Even music celebrities make a point of visiting these hallowed grounds. Bubba Sullivan told me at his store, Bubba’s Blues Corner record store on Cherry Street, that one day he noticed a man with long curly blond hair looking through the store’s record racks. When the man turned around, Bubba recognized that the man was Robert Plant. Plant is just one of many rock and roll musicians who appreciate the history of this Delta town.

The 2005 festival was the first year that it was named the Arkansas Blues and Heritage Festival. The SBBS was forced to drop the King Biscuit name last summer when they could not come to an agreement with the King Biscuit Entertainment Group (KBEG) based in New York on the use of the name. KBEG has owned the trademark of the name “King Biscuit” since the 1970s.

It was a pleasure to spend a little time with Sonny Payne. The man is part of the monumental events that took place here. He genuinely appreciates the part he played as the King Biscuit Time announcer and as an ambassador of Delta blues, yet he is modest about his role and emphasized the importance of always keeping his feet firmly on the ground, maintaining a good work ethic, and keeping life in the right perspective. During our visit, he reminisced about his early days at KFFA, his friendships with Robert Jr. and Sonny Boy, his military service in World War II, and blues stories of Helena.

A poignant moment of the interview was when I asked Sonny about the day Sonny Boy died.

“They were at my brother-in-law’s brother’s store jamming one night. Then they came back to Helena and jammed with a bunch of guys until about three o’clock in the morning and Sonny Boy was as high as Georgia pine.”

Ten minutes before the radio show’s broadcast the next day, Payne was in the studio with Dudlow Taylor, Peck Curtis, and Houston Stackhouse.

Payne asked, “Peck, where’s Sonny Boy? He was going to be on the show today.”

“I’ll run down and get him.” Sonny Boy lived two blocks from the station radio.

When Peck came back, tears were flowing down his eyes. “Sonny Boy’s dead, Mr. Sonny.”

“What are you talking about?”

“He’s dead. They’re taking him out now. . . . Mr. Sonny, I can’t play.”

“Peck, let me tell you something. I’ll say ‘due to unforeseen circumstances, Sonny Boy will not be on the show today.’ We’re not going to announce it because Mattie is over in Mississippi. Get on back in the studio and just play anything.”

“Mr. Sonny, that’s gonna be hard to do.”

“Peck, you’re getting paid for this. Mr. Moore is going to cancel the whole thing if you don’t do something.”

Payne said, “They went on and they cried through the whole damn thing.”

Visiting Sonny Boy

I’m goin’ home. (Whrp whrp whrp)

I’m gonna bring it on home, now. (Whrp whrp)

I’m gonna bring it on home, now. (Whrp whrp whrp)

I’m gonna bring it on home, now. (Whrp whrp)

On another day during that same trip to Helena, I set out to do what was my original purpose for coming to the Delta blues’ heartland: I wanted to find Sonny Boy’s final resting place and pay my respects to him. I drove into Tutwiler, Mississippi, in the late afternoon. Tutwiler is only a little more than two square miles with about 1,400 residents. I thought I would have no problem finding the Whitfield Church cemetery where Sonny Boy was buried. What I did not realize until I arrived in Tutwiler was that the church burned down in 2000.

Although the town is now economically slow like many other small Mississippi Delta towns, it is nevertheless an important landmark for blues fans. Upon approaching the northern edge of town on Highway 49 from Clarksdale, you see the Tallahatchie County Correctional Facility on the right side of the highway and just before a water tower that has inscribed, “Tutwiler, Mississippi – Where The Blues Was Born.” As I drove up and down the streets, I saw houses that were either modest or run down. Several of them were in need of repair. There were a few small stores in old buildings. Only a couple of times did I see people in front of their houses, driving in their cars, or walking along the streets.

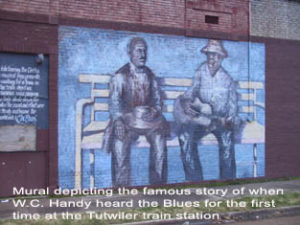

A railroad track went through the center of town. There was not much to see here other than a couple of small stores, a few old buildings with offices and a small park that ran along the side of the railroad track. On the northern side of the track was mural that commemorated the important historical blues event that took place on this very spot in 1903.

A hundred years ago, there stood a train station where traveling band musician, W.C. Handy, waited on a late-night train that was nine hours late. While he waited, a black man in worn-out clothes sat down beside him and began playing a guitar by pressing a knife against the strings which gave a moaning sound. Handy later said that this music was “ the weirdest music I have ever heard.” The man sang the same words three times, “Goin’ where the Southern cross the Dog.” Each line was answered by the sliding sad sounds of the guitar. When Handy asked what the line meant, the man explained that in Moorhead, a town about an hour south of Tutwiler, the tracks of the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley Railroad, known locally as the Yellow Dog, crossed the tracks of the Southern Railroad. The incident is recognized as one of the, if not the, earliest account of a blues song. Hence the reason for the message on the water tower on the north side of town.

I finally gave up trying to find Whitfield Church on my own so I looked around for someone to help me. Near the railroad tracks in the square was a hospice services office. I asked the receptionist if she could tell me where the church was.

“No, I’ve never heard of it.”

“How about the cemetery where Sonny Boy Williamson is buried?”

“Who? Wait here. Let me ask one of the other women here if she knows.”

She went to an office down the hallway. Moments later, a woman came out of the office with a smile and politely said, “We’re not from Tutwiler. We don’t know where the cemetery is. Why don’t you try the health clinic a few blocks up the road? They may know since they’re from here.”

I drove to the clinic and went inside to ask a young woman if she knew where Sonny Boy Williamson is buried.

“Who?”

“Sonny Boy Williamson. He was a famous blues harmonica player.”

“Wait right here. I’ll ask a friend of mine here. She knows about all that stuff.”

The young lady soon returned with a slightly older woman. The older woman said, “Get in your car and follow us. We’ll take you there.”

I followed the two women out of Tutwiler to the outskirts of the south side of town. We were on a two-lane road in the middle of dormant cotton fields. Soon we came to a few small tombstones set back from the right side of the road. Behind the group of head markers were a few trees and brush. There could not have been more than twenty plots in the small and neglected graveyard. Sonny Boy has the most prominent headstone which was set the farthest back from the road.

The women and I walked through the weeds and up to the man’s grave. They stood with me by the grave for a few minutes as I paused for a moment to reflect what a great man lay here. The older woman pointed out the twin headstones in front of Sonny Boy’s plot. The graves were the resting places of his last two living sisters, Julia Barner and Mary Ashford, who were killed in a fire at Mary’s house in 1995. The Sonny Boy Blues Society had raised half the money for their burials at a fundraiser and Sonny Boy Williamson biographer, William Donaghue, paid the other half.

As we walked back to our cars, I thanked the woman for their help and joked with them for being so brave to come out to a deserted field with a stranger. The older woman mirthfully replied, “Oh, we’re not worried. We’re packin’ some heat. We’re fine.”

My journey was complete. Just six months before, I heard for the first time about this man who made blues history. Now, I knew who he was, what he did, and where a lot of it happened. This experience was a great introduction to blues history and a sentimental journey since it was not far from home. I drove back to Pine Bluff that night through the winding country roads.

Gonna bring it on home,

Bring it on home to you. (Whrp whrp whrp whrp whooooo . . . )